54, did not smoke or drink, and there was no family history of lung cancer. Yet he was diagnosed

with the disease early this year.

As the proportion of smokers in Singapore falls, so has the overall incidence of lung cancer. Yet one issue continues to puzzle doctors: Why are more East Asian women, who have never smoked, getting the disease?

This is certainly the case for Chinese women in Singapore, said Dr T. Agasthian of the Agasthian Thoracic Surgery at Mount Elizabeth Medical Centre.

About 70 per cent of these “never- smokers” – as they are referred to in the medical field – who have lung cancer are women.

About 70 per cent of these “never- smokers” – as they are referred to in the medical field – who have lung cancer are women.

All told, “never-smokers” make up three in 10 lung cancer patients here, according to a study by the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS), and the incidence is rising.

Overall, lung cancer rates among men have come down from 61.2 per 100,000 per year in the late 1970s, to 33.7 between 2010 and 2014.

Some 4,454 men were diagnosed with lung cancer between 2010 and 2014, and among women, the numbers are even smaller.

From 2010 to 2014, 2,399 women got lung cancer. Doctors are not sure why non-smoking Chinese women are increasingly falling victim, but exposure to environmental pollutants would certainly be a factor.

Said Dr Ang Mei Kim, senior consultant medical oncologist at NCCS: “Exposure to second-hand smoke at home or at the workplace, one of the main causes of lung cancer in never-smokers, increases the risk by 25 per cent.

“Another risk factor is environmental pollutants. Studies in Chinese populations show that burning coal and biomass, particularly in poorly ventilated areas, for cooking and heating, may also increase the risk.”

But while this reasoning seems sound, it does not explain everything. Many patients do not have a history of long-term exposure to environmental carcinogens, noted doctors.

Some have theorised that women might be vulnerable because of the amount of wok cooking they do which emits smoke and steam, an as-yet unproven theory.

Close to half of the patients with lung cancer have what is called the EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) mutation.

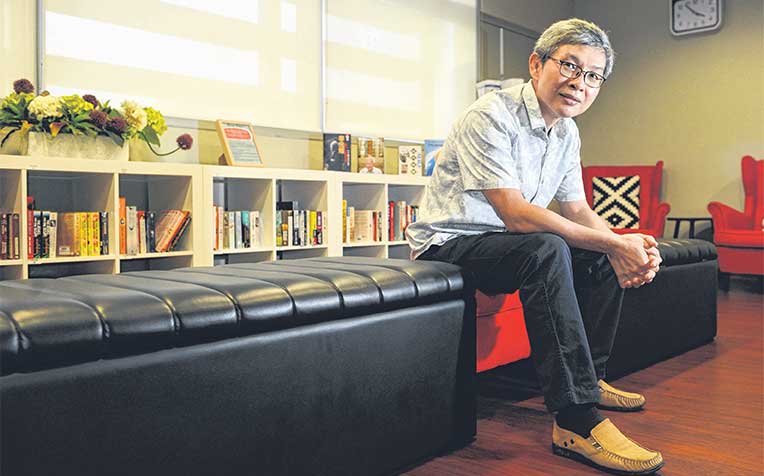

The trend is similar for the rest of Asia, compared to about 20 per cent of Caucasian patients, said Dr Chin Tan Min, a senior consultant in the departmentof haematology-oncology at the National University Cancer Institute Singapore (NCIS).

But targeted therapy has been developed for the EGFR mutation, which prolongs the survival rates.

About a decade ago, an additional one totwoyears of extended survival would have been optimistic, said Dr Chin. But now, it is up to three years with targeted drugs that help to control the tumour from spreading and any symptoms arising.

It comes at a price.

Drugs targeted at the EGFR mutation cost about $3,000 to $4,000 a month, on average, said Dr Agasthian and Dr Chin.

For lung cancer patients whose condition is caused by smoking, immunotherapy – the latest treatment in medicine using the immune system to fight cancer cells – is more effective, said Dr Chin.

Immunotherapy prolongs survival rates for quite a few months over chemotherapy, according to preliminary data, said Dr Chin.

But the new treatment now costs patients about $15,000 a month, if not more. How many months of treatment they require depends on how they respond. As it is a new therapy, it is not subsidised, but patients can make a claim under their private insurance plans.

Get it on Google Play

Get it on Google Play