General practitioners are key to identifying potential thyroid malignancies. The SingHealth Duke-NUS Head & Neck Centre shares more about the latest in assessment and treatment options, and when specialist referral is needed.

Thyroid nodules are usually incidentally picked up during health screenings in the primary care setting. General practitioners are therefore key to initiating investigations to identify potential malignancies. Find out more about the latest in assessment and treatment options, and when specialist referral is needed.

INTRODUCTION TO THYROID NODULES

The occurrence of thyroid nodules is very common, and

it has been shown that nodules can be detected with

ultrasound (US) in up to 68% of a random population,

with increased incidence in females and the elderly1.

Most of these patients with thyroid nodules are

asymptomatic, with the nodules being picked up

incidentally on routine head and neck imaging for

other conditions, or via US done during health

screening in the primary care setting.

Incidence of thyroid cancer

Fortunately, the vast majority of thyroid nodules

(> 95%) are benign and do not cause problems in

the patients’ lifetimes. Congruent with the increased

detection of thyroid nodules, the incidence of thyroid

cancer is also increasing globally.

In Singapore, thyroid cancer is the eighth most

common cancer amongst females, with an incidence

of 10.9 per 100,000 individuals. Of note, amongst

younger females less than 50 years of age, it ranks in the top three commonest malignancies.

The priorities in the evaluation of patients with

thyroid nodules will therefore be to exclude

malignancy and to identify symptomatic patients

who may benefit from intervention.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Figure 1 shows the symptoms, signs and red flags to look out for in the presentation of thyroid nodules.

| Symptoms and signs | Red flags |

Anterior neck swelling:

Dominant nodule, goitre Compressive symptoms:

Dysphagia, dyspnoea

(typically worse when lying down) Hormonal dysfunction:

Symptoms/signs of thyrotoxicosis or hypothyroidism Assess for risk factors:

Previous neck irradiation, family history

of thyroid malignancy

| Voice hoarseness Rapidly enlarging swelling Presence of lymphadenopathy Significant compressive symptoms –

airway distress Fixation of nodule to surrounding tissues

|

Figure 1

TYPES OF INVESTIGATIONS

1. Thyroid function test

When it is needed

A thyroid function test (TFT) should be performed

in the initial assessment of a patient with a thyroid

nodule or goitre, especially if they have symptoms

suggestive of thyroid hormonal dysfunction.

Managing thyroid hormonal dysfunctions

The treatment of hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism

can be initiated in the primary care

setting and these patients can continue to follow

up with their general practitioners once their

thyroid function is controlled.

For patients with thyroid functions that are more

difficult to control, or in the presence of red flags or

atypical features, referral for specialist evaluation

should be considered.

2. Thyroid ultrasound

When it is needed

A US of the thyroid with evaluation of lymph nodes

should be performed in all patients presenting with

thyroid nodules or goitres.

Objectives

The objectives of ultrasonography are to:

- Confirm the clinical diagnosis

- Evaluate the size of the nodules/goitre

objectively (allowing a baseline for

surveillance)

- Assess for suspicious features that will

necessitate further investigation with a fine

needle aspiration cytology

Standardised scoring system

However, US reports, until recently, lacked standardisation

and can be difficult to interpret. Tracking nodules across various time points can also be

challenging.

Since mid-2022, the reporting of US thyroids

in SingHealth has followed a similar format

regardless of performing institution. Nodules are

labelled the same way on follow-up scans.

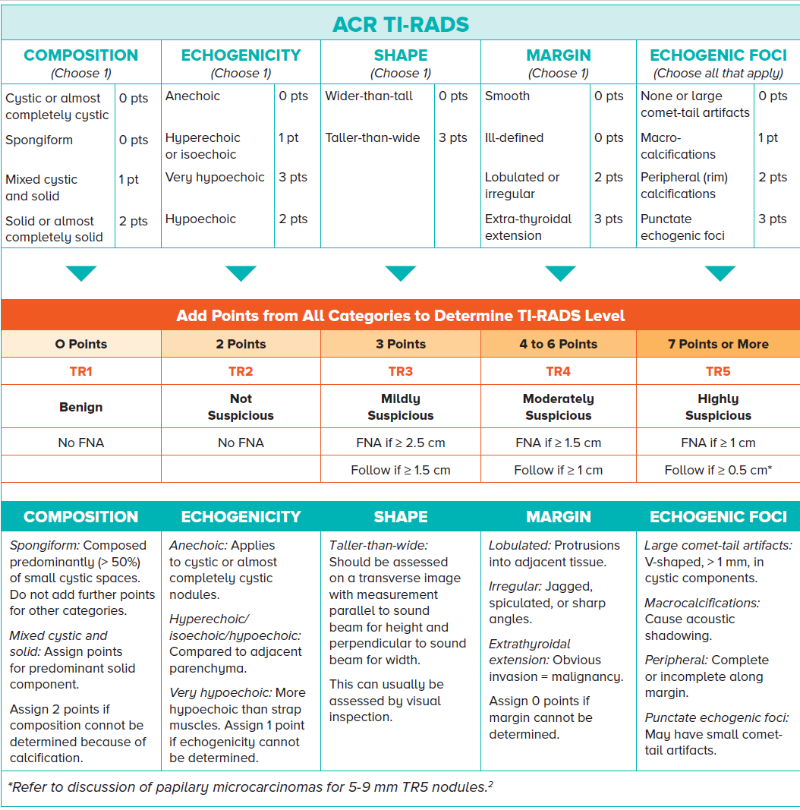

In addition, nodules are now reported according

to the Thyroid Imaging Reporting & Data System

(TI-RADS)2 (Figure 2) . TI-RADS is a scoring system

which has been validated for reproducibility with

clear criteria for nodule sampling, allowing a more

streamlined approach. There is also evidence to

show that it has reduced sampling rates.

Figure 2

3. Fine needle aspiration cytology

When it is needed

The introduction of TI-RADS in thyroid sonography

has provided a standardised and objective tool

for thyroid nodule assessment, thereby reducing

ambiguity around which nodules require cytologic

evaluation.

Suspicious nodules are further investigated with

fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC).

Procedure and reporting

In this procedure, which can be US-guided, a

needle is introduced into the nodule to collect

cells. This is generally a safe procedure and can

be performed as day surgery.

The FNAC results will then be reported by the

pathologists using the Bethesda system3 (Figure

3), which estimates a higher risk of malignancy

with corresponding higher Bethesda grading.

This then provides the attending clinician with a guide for counselling the patient regarding the

management options and recommendations.

Nondiagnostic/unsatisfactory -

Cyst fluid only

- Acellular specimen

- Other: Obscuring factors

| 5 - 10% | 5 - 10% | Repeat FNA under

US guidance |

Benign -

Benign follicular nodule

- Chronic lymphocytic (Hashimoto) thyroiditis, in proper clinical setting

- Granulomatous (subacute) thyroiditis

| 0 - 3% | 0 - 3% | Clinical and US follow-up until two negative |

| Atypia of undetermined significance /

follicular lesion of undetermined significance | 6 - 18% | 10 - 30% | Repeat FNA, molecular testing or lobectomy |

| Follicular neoplasm / suspicious for a follicular neoplasm (Specify if Hurthle cell type) | 10 - 40% | 25 - 40% | Molecular testing,

lobectomy |

| Suspicious for malignancy | 45 - 60% | 50 - 75% | Lobectomy or near-total thyroidectomy |

Malignant - Papillary thyroid carcinoma

- Medullary thyroid carcinoma

- Poorly differentiated carcinoma

- Undifferentiated (anaplastic) carcinoma

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Carcinoma with mixed features

- Metastatic malignancy

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Other

| 94 - 96% | 97 - 99% | Lobectomy or near-total thyroidectomy |

Figure 3 2017 Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology

NIFTP: Non-invasive follicular thyroid neoplasm

MANAGEMENT OPTIONS

1. Ultrasound surveillance

As the majority of thyroid nodules are benign

and indolent, and do not cause symptoms, they

can generally be monitored with US surveillance. These include:

- TR3-5 nodules that may not meet the size

criteria for FNAC

- FNAC-proven benign nodules and for which

patients are asymptomatic

Follow-up screening recommendations

As the risk of malignancy increases with higher

TI-RADS grading, the recommended frequency of

performing US thyroid surveillance is as follows:

TR1-2 nodule: US surveillance is not routinely

required, especially for asymptomatic patients.

Patients may be advised to observe themselves

and return if symptomatic.

TR3 nodule: Follow-up at 1, 3 and 5 years

TR4 nodule: Follow-up at 1, 2, 3 and 5 years

TR5 nodule: Annual follow-up till 5 years

2. Surgery

Thyroidectomy is a common and generally safe

head and neck surgical procedure and may be

indicated for some patients who present with

thyroid nodules or goitres.

The extent of surgery will either be a hemithyroidectomy

(lobectomy) or a total thyroidectomy.

In addition, for cancer cases, additional surgical

procedures may be performed as indicated (e.g.,

neck dissection for lymph node clearance).

Indications

The indications for surgery are:

- Proven or suspected thyroid malignancy

- Benign nodules/goitres causing compressive

symptoms

- Thyrotoxicosis resistant to medical therapy

- Patient preference

Surgical methods

a. Traditional neck incision

The majority of thyroidectomies are performed

via the traditional neck (transcervical) incision.

This surgical approach is well-established and

provides the most direct access to the thyroid

gland, thereby allowing safe instrumentation to remove the thyroid gland while preserving

vital adjacent structures such as the recurrent

laryngeal nerve and the parathyroid glands.

Although this approach invariably requires a

neck scar, the majority of cases heal very well

and are usually not conspicuous with time.

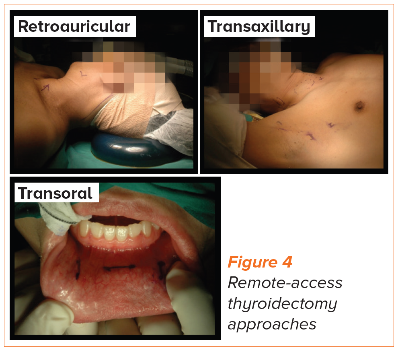

b. Remote-access procedures

Remote-access approaches (e.g., transaxillary,

retroauricular or transoral approaches) avoid

an anterior neck scar but surgical access to the

thyroid gland is not as direct, requiring a wider

extent of dissection and longer operative times.

These approaches may not be suitable for

certain patients such as those with larger

nodules/goitres or thyroid malignancy. Careful

patient selection with thorough counselling is

therefore imperative for patients who may be

keen on these remote-access procedures.

3. Thyroid nodule ablation

Thyroid ablation, first introduced in Singapore in

2017, has been shown to be effective in treating

symptomatic benign thyroid nodules.

This procedure involves introducing a small probe

into the nodule, after which heat is generated to

ablate (or destroy) the tumour. Size reduction of

the nodule then takes place slowly over months.

The most common technology used is that of

radiofrequency ablation (RFA). It is minimally

invasive, can be performed as day surgery and is

shown to be effective in shrinking benign nodules.

Selected patients with small papillary thyroid cancers who cannot undergo surgery may also be

candidates for thyroid nodule ablation.

Thyroid nodules are very common, and there

currently are guidelines in place within

SingHealth institutions for the attending physicians

to manage them in a timely and safe

manner. What GPs can do

Many of these patients can be monitored in

the primary care setting, typically those who

are asymptomatic with nodules that have been

assessed to be benign (TR1-2, FNAC-proven) or

have been stable on serial US. When to refer to a specialist

Indications for referral to specialist care will

include: - Patients who are symptomatic or have

red flag features

- Larger nodules (> 4 cm)

- Increase in size of nodules during

surveillance (> 20% increase in two

dimensions)

|

REFERENCES

2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines

for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated

Thyroid Cancer.

Tessler FN, et al. ACR Thyroid Imaging, Reporting and

Data System (TI-RADS): White Paper of the ACR TI-RADS Committee. Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2017

May;14(5):587–959.

Ali SZ, Cibas ES. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid

Cytopathology, 2nd ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017.

Dr Too Chow Wei graduated from the Faculty of Medicine, National University of Singapore

in 2003. He subsequently trained at various hospitals in Singapore in the diagnostic

radiology training programme and attained specialisation accreditation in 2012.

He is currently a Senior Consultant at the Department of Vascular and Interventional

Radiology and the Director of Interventional Services at Singapore General Hospital. He

has a keen interest in the realm of interventional oncology and palliation, with experience

in the ablation of liver, lung, kidney and bone tumours.

Dr Tay Ze Yun graduated from the National University of Singapore and received his

medical degree from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine in 2008. He subsequently joined

the SingHealth Otolaryngology Residency Programme as part of the inaugural batch of

residents and completed his specialist training in 2016.

In pursuit of his sub-speciality interest in head and neck surgery, he completed the two-year

SingHealth Duke-NUS Head & Neck Centre Fellowship Programme (2016-2018).

He was subsequently awarded the Ministry of Health’s Health Manpower Development

Plan award in 2018 to pursue a surgical fellowship in advanced head and neck surgical oncology at the world-renown Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taiwan.

Dr Tay also completed the International Federation of Head and Neck Oncologic

Societies fellowship and graduated with honours in 2020. He is currently a Consultant at

the Departments of Otorhinolaryngology –Head & Neck Surgery at Sengkang General

Hospital and Singapore General Hospital.

GPs can call the SingHealth Duke-NUS Head & Neck Centre for appointments at the following hotlines:

Singapore General Hospital: 6326 6060

Changi General Hospital: 6788 3003

Sengkang General Hospital: 6930 6000

KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital: 6692 2984

National Cancer Centre Singapore: 6436 8288

National Dental Centre Singapore: 6324 8798