A procedure which destroys certain nerves in the kidney helps bring down blood pressure in patients who do not respond well to drugs.

A procedure which destroys certain nerves in the kidney helps bring down blood pressure in patients who do not respond well to drugs.

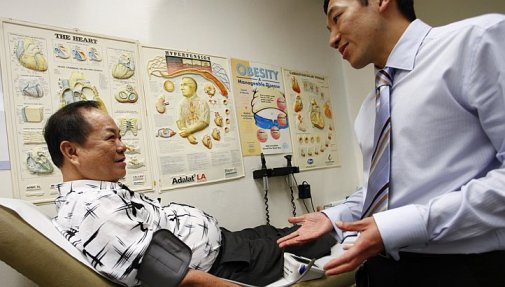

Dr Chin Chee Tang, a consultant at the department of cardiology at National Heart Centre Singapore, checks the blood pressure of retiree Leow Cheng Hai, 62. Mr Leow is one of six patients who have undergone renal denervation in four hospitals here to battle hypertension that is resistant to medication.

Retiree Leow Cheng Hai, 62, has fought hypertension, or high blood pressure, for three decades.

It seemed to be a losing battle earlier this year when his blood pressure showed no sign of letting up even though he was popping four different types of medication.

The former fruit seller's systolic (maximum) blood pressure hovered between 170 and 180 millimetres of mercury (mmHg), well above the target of 130mmHg for a person with diabetes.

With each increment of 20mmHg in systolic pressure, Mr Leow's risk of cardiovascular disease doubled, said Dr Chin Chee Tang, a consultant at the department of cardiology at National Heart Centre Singapore (NHCS).

Normal blood pressure is presently defined as below 130/80mmHg, where the first figure represents systolic blood pressure and the second, diastolic blood pressure.

Hypertensive patients should get their blood pressure below 140/90mmHg, and diabetic hypertensive patients even lower, to 130/80mmHg, said Associate Professor Lim Soo Teik, head and senior consultant at the department of cardiology at NHCS.

But for Mr Leow, there was nothing more doctors could do for him.

Then, in September, his doctor offered him a new option: renal denervation.

In this minimally invasive procedure, radiofrequency waves are used to destroy the nerves in the renal arteries which play a vital role in modulating blood pressure (see graphics).

A week before the procedure, Mr Leow's systolic blood pressure peaked at 190mmHg. Two weeks after his operation on Sept 26, it was down to 150mmHg and stayed in that region even a month later, said Dr Chin, who performed the procedure with Prof Lim and two other cardiologists.

Doctors say renal denervation is a breakthrough in the treatment of such stubborn hypertension.

Though it will not cure high blood pressure, early studies suggest destroying sections of the renal nerves may reduce blood pressure by about 32/12mmHg when patients were checked six months after the procedure.

Patients will not have such a hill to climb in their attempts to bring their blood pressure levels down and, like Mr Leow, they may even be able to reduce the amount of medication they are on.

Mr Leow is now taking three types of medicine instead of four.

Mind Your Body understands that six patients, including Mr Leow, have undergone the procedure at four hospitals here - NHCS, Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH), Raffles Hospital and Changi General Hospital (CGH).

It is definitely beneficial for hypertensive patients to reduce their blood pressure, said NHCS's Prof Lim.

A mere 5mmHg drop in systolic blood pressure can reduce the risk of stroke by 14 per cent, heart disease by 9 per cent and death by 7 per cent.

One quarter of the population has hypertension, putting such people at risk of stroke and cardiovascular disease, two of the top killers here. Of these, 10 per cent have a resistant form of the condition.

Despite changes to lifestyle and diet and medication, these patients find it nearly impossible to bring their blood pressure under control.

Many are on multiple drugs and even if they take on one or two more, they will see their blood pressure drop by just another 5 to 10mmHg, said Dr Chin.

The concept of disrupting the nerves that link the brain, heart and kidneys responsible for regulating blood pressure was born in the 1930s, said Dr Yang Wen Shin, a nephrologist at Raffles UroRenal Centre at Raffles Hospital.

But the procedure became feasible only in the 1950s and required open surgery, which often resulted in adverse effects.

Too many patients ended up with unacceptable complications such as urinary incontinence and sexual dysfunction, making the procedure too risky, Dr Yang added.

It was abandoned in favour of anti-hypertensive drugs.

Recent technology, however, has made it much safer and it is now being used in places like the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, Malaysia and Hong Kong, said Prof Lim.

The initial studies look promising.

A multi-centre study published in the Lancet medical journal in December last year found that the blood pressure of 49 patients who had renal denervation dropped by 32/12mmHg from 178/96mmHg after six months.

In contrast, 51 other patients who did not have the denervation had virtually no change to their blood pressure after six months.

Nearly 40 per cent in the renal denervation group achieved a systolic blood pressure target of less than 140mmHg, compared to 6 per cent in the control group.

Twenty per cent in the renal denervation group were also able to reduce the amount of medication they were taking, compared with 6 per cent in the control group. Both groups of patients were taking the same number and types of anti-hypertensive drugs.

None of the patients had serious complications from the procedure.

Still, this was a small study with no long-term results, said Associate Professor Adrian Low, a senior consultant at the cardiac department at the National University Heart Centre, Singapore.

He said one concern is that burning off the nerves may not destroy them permanently as animal studies have shown that nerves do grow back. If they did, it would mean a recurrence of the uncontrolled hypertension.

But rather than wait for years to see if this does happen, Prof Low said there is merit in using this new therapy now.

It could benefit several thousand people in Singapore.

According to Adjunct Assistant Professor David Foo, head and consultant at the department of cardiology at TTSH, 10 to 20 per cent of the more than 3,000 hypertensive patients treated in the hospital each year will have resistant hypertension.

Studies also show that between 5 and 10 per cent of the hypertensive population have resistant hypertension, said Dr Gerard Leong, a consultant at the department of cardiology at CGH.

But before patients are deemed to have resistant hypertension and offered the procedure, doctors first have to rule out some of the possible reasons a patient's condition is not managed well, said Raffles Hospital's Dr Yang.

Some patients may not be taking their medicine because of unpleasant side effects like dizziness and coughing, so some adjustments to the drug regimen could be made.

In other instances, they may have underlying medical conditions like kidney diseases or tumours, which need to be treated first in order to control the blood pressure.

There is also something called 'white coat hypertension', said Dr Leong.

That is when the blood pressure rises because of the anxiety of being in a clinic, giving a falsely high reading.

However, once all these issues have been dealt with, Dr Yang said all patients who fail to reach their blood pressure target goal despite being compliant with adequate use of medication should be considered for renal denervation.

So far, costs for the operation are quite high. Doctors say this is the case with any new procedure, but costs are likely to come down in future.

At Raffles Hospital, the cost of surgery and a night's hospitalisation is between $14,000 and $15,000.

At NHCS, the cost of the single-use catheter alone would be between $7,000 and $9,000. Two days of hospitalisation for subsidised patients will come up to $3,000 to $4,500.

CGH said it was too early for them to disclose the cost of the procedure, while TTSH said the cost of the procedure ranges from $5,000 to $10,000. Financial assistance is available for patients on a case-by-case basis.

The Silent Killer

The condition is called a silent killer because sufferers often show no obvious symptoms.

The only way to tell if a person has high blood pressure is to have it checked.

But someone with extremely severe hypertension may experience symptoms such as dizziness, fatigue and problems with vision.

This is why it is not unusual to pick up hypertension only when complications such as a stroke or heart attack set in.