KKH shared on the importance of monitoring a child’s growth and that it can also guide healthy nutrition during childhood to prevent obesity and stunted growth.

Knowing how to assess that may allay parents' fears over their kids' size, allow them to seek help if needed

Many parents think they know how to spot obesity, yet they easily fail to notice it in their own children.

However, if their child is significantly bigger (or smaller) than his peers, they inevitably worry that he is overweight (or underweight). This can lead to inappropriate restrictions on food intake or overfeeding.

"A child's size matters to parents and may give rise to anxiety, especially when comparisons are being made with the child's peers," said Associate Professor Fabian Yap, the head and senior consultant at the endocrinology service of the department of paediatrics at

KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital.

"These anxieties are real to parents, even though many of these children have normal growth."

This is why children's growth should be monitored. The process provides objective measures of growth and may allay these concerns while enabling healthcare professionals to identify excessive weight or height gain, or other abnormal growth patterns that suggest underlying disease, he said.

It can also guide healthy nutrition during childhood to prevent obesity and stunted growth, added Dr Yap, who co-wrote a new paper from the College of Paediatrics and Child Health of the Academy of Medicine Singapore, titled Growth Assessment And Monitoring During Childhood.

The paper aims to clarify the purpose of growth monitoring and provides recommendations for physicians to assess and manage growth in infants and children.

The paper aims to clarify the purpose of growth monitoring and provides recommendations for physicians to assess and manage growth in infants and children.

"In addition to comparison with population norms, assessment of height is compared with genetic or biological potential and assessment of weight is then compared with the child's height," said Dr Yap. These measurements are then tracked over time to assess growth, he said. Such monitoring would serve to reassure parents when growth is normal.

Quite a lot of them would be thankful, going by a survey conducted by the Singapore Nutrition and Dietetics Association and Abbott in June. It found that many parents do not understand what normal growth is.

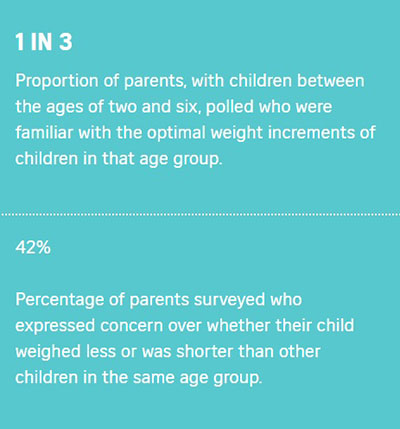

The survey polled 1,002 parents with children between the ages of two and six about their knowledge of expected annual height and weight increments, and the impact of nutrition on immunity and growth.

Only one in three was familiar with the optimal weight increments, while about 46 per cent of the respondents were aware of the annual height increments for children in this age group.

About 42 per cent of the parents expressed concern over whether their child weighed less or was shorter than other children in the same age group.

Dr Yap said parents should at least be made aware of their child's weight and BMI (body mass index) status as these are objective measures that can be tracked. He pointed to a 2016 local study which showed that more than half of Singaporean mothers of underweight children overestimated their child's weight status, while more than 75 per cent with overweight children underestimated weight status.

These errors of perception are one reason for inappropriate nutrition practices, he said.

"Parents should be made aware that good growth matters at each stage of their child's life so that an optimal final height can be achieved," said Dr Yap.

"Parents should also be made aware that growth encompasses both height and weight growth and that the relationship between weight and height is important."

Dr Yap warns that excessive nutrition during childhood may improve height growth, but may also lead to obesity. "Lastly, parents should be made aware that height growth is highly influenced by genetic potential. However, weight gain is highly influenced by lifestyle and habits, and can continue beyond final height."

Final height is attained by 18 years of age.

Dr Janice Wong, a paediatrician and specialist in neurology, neurorehabilitation and neurodevelopment at Thomson Paediatric Centre, said the West faces problems of improper nutrition but in Singapore, the main issue is that many parents are not sure how to assess growth.

They may also have a skewed view of what is considered healthy. "They think chubby babies equal healthy babies. It's a very Asian thing," she said.

Therefore, a lean baby may be perceived as showing poor growth.

"I have had parents come to me and they say: 'My kid is too skinny.' But the kid is all right and growing normally," said Dr Wong.

A child's development is not related to size, as he can be small-or big-boned. It is the nutrition that he gets that matters, she noted.

"Some kids just like to snack but don't eat proper meals," she said. They can eat poorly for weeks and, if this continues, the child will end up not taking in enough food varieties, which will result in micro-nutrient deficiencies, she said.

There are parents who worry whether their babies are getting enough milk, but most babies know when to stop drinking milk, and it is the parents who want them to drink a certain amount, said Dr Wong.

"For instance, after six months, they are supposed to sleep through the night but some parents will stuff a bottle of milk into their mouths up to three times a night. These babies then learn how to sleep on milk."

Babies typically roughly double their birth weight by six months of age and triple it by the end of their first year. "If your baby's weight is at the 10th percentile, they can't be growing to the 90th percentile in six months, as this would mean they are growing too fast," said Dr Wong.

When they grow too fast, it is usually a result of overfeeding or a medical problem. "If a child is growing too fast, the risk of metabolic syndrome is very high. This puts a stress on their organs."

If they continue to be obese, by the time they are in their 20s, they can end up with early diabetes, high blood pressure and other problems.

Dr Wong said some children may have intermittent nutritional issues if they were to fall sick every month. They may need vitamin supplements, so their parents should seek guidance from healthcare professionals. "You cannot peg a child's growth by comparing him with his peers, you must monitor it," she said.

One way of doing so is to check growth charts published by the Health Promotion Board.

"As long as the child stays within the growth curve, he is fine. If his weight drops too much too soon or if he is off the charts,

then he is not fine," she said. "It's important for parents to know about normal growth so they can seek help when needed."