Sacral neuromodulation gives patients enhanced quality of life and restores their independence.

Mr Leong used to dread going out. He suffered from urinary incontinence, which meant he was unable to reach the toilet in time when he felt the urge to urinate. He often wet himself as a result. But after undergoing a procedure known as sacral neuromodulation, he is happily free of that problem.

He had sought treatment for another issue — he often woke up in the night needing to go to the toilet, but wasn’t able to pee. He had a urinary retention problem, which meant that although his bladder was full, he was not able to empty it due to a dysfunction in the muscles that control urination.

He had sought treatment for another issue — he often woke up in the night needing to go to the toilet, but wasn’t able to pee. He had a urinary retention problem, which meant that although his bladder was full, he was not able to empty it due to a dysfunction in the muscles that control urination.

Tests later found that he also suffered from urge incontinence due to an overactive bladder.

“I didn’t feel the need to pee. But when that sensation came, it was too late to get to the bathroom,” said Mr Leong.

“When my friends asked me to join them at the coffee shop, I declined because I didn’t want to walk around with wet pants.”

Now, his life has been transformed. “I’m very happy because there’s no more leakage, and no more incontinence problem.”

In better control

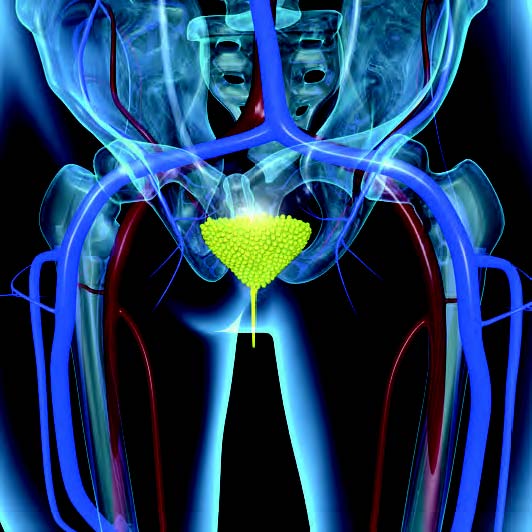

Sacral neuromodulation involves implanting a small pacemaker-like device into the sacral area, which is at the end of the spine. The device sends electrical impulses to stimulate the nerves located in the lower back, just above the sacral area. The specific sacral nerves involved are the third and fourth, which regulate bladder and bowel activity. The intensity and frequency of the pulses can be modified by both the physician and the patient through an external programmable device.

Although it is little known and isn’t offered widely in this region, sacral neuromodulation is a well-established procedure in the West, having been introduced some 20 years ago to treat urinary incontinence. The procedure benefits specific types of urinary incontinence, such as overactive bladder or urge incontinence, and patients whose faecal incontinence is due to anal sphincter muscle weakness or defect, pelvic nerve injury, or weakness.

Patients whose condition isn’t helped by medication and who aren’t keen on surgery can be offered this option. After they are evaluated and have met certain criteria, patients go through a short trial phase. If the device is found to be effective, they can have the device permanently implanted, said Dr Tricia Kuo, Consultant, Department of Urology, Singapore General Hospital (SGH).

Patients whose condition isn’t helped by medication and who aren’t keen on surgery can be offered this option. After they are evaluated and have met certain criteria, patients go through a short trial phase. If the device is found to be effective, they can have the device permanently implanted, said Dr Tricia Kuo, Consultant, Department of Urology, Singapore General Hospital (SGH).

At SGH, the procedure has been available since 2010, but it was only in recent years that it has gained interest among patients. Since 2015, eight patients have had the device implanted permanently — five for urological conditions and three for faecal incontinence.

According to Dr Cherylin Fu, Senior Consultant, Department of Colorectal Surgery, SGH, patients under the trial phase have to record the number of incontinent incidents, such as soiled underwear or leakages. The data are compared with that before they went on the trial, and the device is considered effective if patients get at least a 50 per cent reduction in the number of incidents.

“Patients can be very effectively treated, with up to 76 per cent reduction in their overactive symptoms, and faecal incontinence symptoms reduced by at least half in 70 to 80 per cent of patients,” said Dr Fu.

In Singapore, 10 to 40 per cent of the population is estimated to suffer from some form of urinary incontinence, and 4.7 per cent from faecal incontinence.

Although the number of patients who have undergone the procedure at SGH may be relatively small, “sacral neuromodulation has made significant difference in the quality of life for patients, restoring function and independence,” said Associate Professor Emile Tan, Head, Department of Colorectal Surgery, and Director of the Gastrointestinal Function Unit, SGH.

Mr Leong, for one, has been able to get better sleep than before. Compared to having to wake up every one to two hours previously, he is now able to sleep for about five hours at a stretch.