A 35 year-old man (A) had slumped over while watching television and became unresponsive. His wife who was next to him at the time, checked his pulse and could not detect any movement. She quickly dialled for the ambulance and began life-saving cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) on him for approximately eight and a half minutes.

When the ambulance arrived, the man was found to be in ventricular fibrillation (a condition when there is rapid or chaotic heartbeat due to the heart’s ventricles beating too fast and losing its pump function) with no blood pressure.

He was quickly defibrillated (electrically shocked back into a normal rhythm), following which he made a full recovery. His initial diagnostic tests including the electrocardiogram (ECG), coronary angiogram and echocardiogram all appeared normal. He was then referred to the ICC clinic at NHCS.

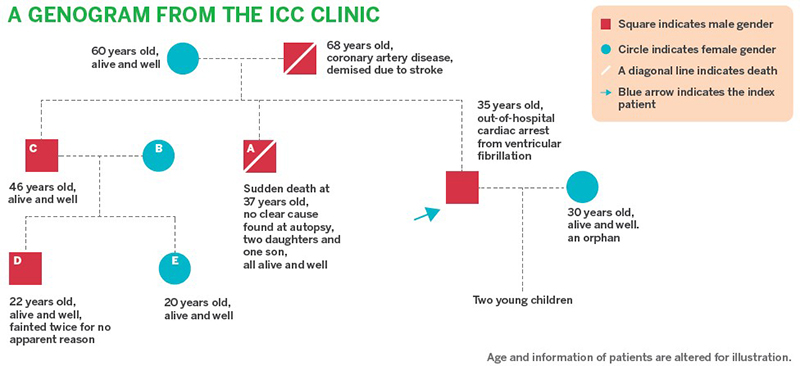

At the ICC clinic, the care team carefully looked at the tests he had undergone, and conclusively agreed that they appeared entirely normal. Looking at the patient’s detailed family history, a genogram was also constructed, which is a diagram showing the relationship between family members and any relevant manifestations of disease that they might have (refer to Figure 1).

Figure 1. Case study's genogram – a diagram on the relationship between family members and any relevant manifestations of disease that they might have

Figure 1. Case study's genogram – a diagram on the relationship between family members and any relevant manifestations of disease that they might have

This was the first and most important clue, as the genogram revealed that the patient had a brother (B) who had died suddenly at the age of 37, and although an autopsy was done, no clear cause was pinpointed. In addition, he had a nephew (D) who had fainted twice for no apparent reason, and injured himself as a result.

With this background, the team were concerned by a number of arrhythmia syndromes that could cause sudden death – these are electrical disorders of the heart and include long QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, early repolarisation syndrome and idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. The patient therefore underwent a number of specialised tests including one called a flecainide challenge. This is a test using a drug to deliberately provoke a condition called Brugada syndrome.

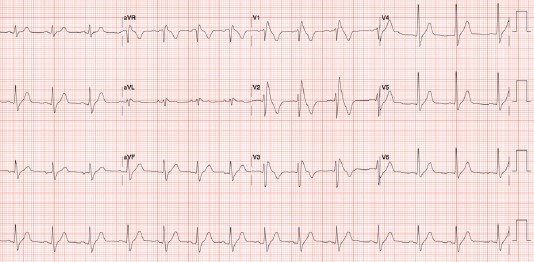

Within one minute of starting the flecainide infusion, the patient’s ECG became floridly abnormal (Figure 2) and further infusion of the drug was immediately stopped. This type of severe ECG change occurring so quickly essentially confirmed the diagnosis of Brugada syndrome and established the cause for the ventricular fibrillation and the collapse in the patient. It inferred that the likely cause of death of his brother (B) was undiagnosed Brugada syndrome.

Figure 2. An ECG of the patient, the minute after starting flecainide infusion

The appropriate advice and treatment for Brugada syndrome was given to the patient, including implantation of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) to protect against possible future episodes of ventricular fibrillation.

At the ICC clinic, with such a background of family medical history, the patient was offered a test for genetic abnormalities that can cause Brugada syndrome. This was particularly the case because he has two children, plus a nephew who had prior history of fainting twice. The care team proceeded with a genetic test withstanding that it might be difficult to interpret Brugada syndrome as the mutations of the gene - SCN5A, which was thought to be responsible for Brugada syndrome, only happened 25% of the time. The results found a likely mutation in SCN5A.

With this insight into the genetic material of the patient, a screening test for Brugada syndrome was then offered to other members of his family. A consultation with other family members was arranged, particularly for the patient’s brother (C) and his two children (D and E). All three of them (C, D and E) agreed to be tested.

The results later showed that while C and D were found to carry the SCN5A mutation but E was not affected. In view that the patient's two children were very young, the team suggested to defer testing until later age. The results from the screening test were very useful information that allowed the care team to counsel, treat and follow up with the patient’s immediate and extended family in the most appropriate manner, for better care of their medical health.

Conclusion

While the ICC clinic is a new service at the NHCS, it provides domain expertise in the diagnosis and management of genetic conditions affecting the heart. The clinic offers specialist tests to diagnose these conditions, both genetic and non-genetic.

For genetic testing, the clinic offers pre-test counselling, interpretation of the genetic test and follow-up, including screening of close and extended family, as part of the early diagnosis plan.