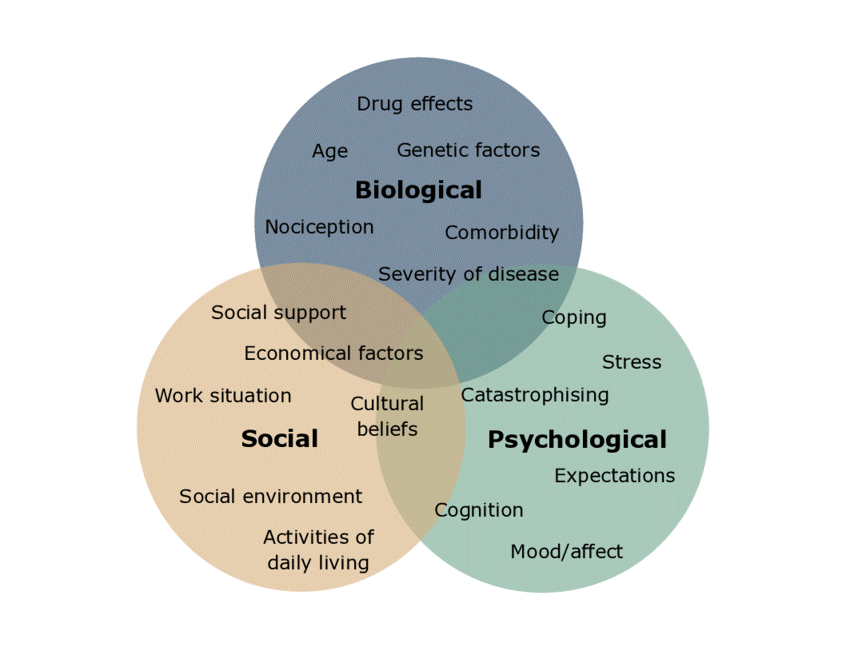

Chronic pain is broadly defined as pain that persists beyond normal tissue healing time, which is generally taken to be three months. Research literature suggests that chronic pain is a result of complex interactions between health and non-health factors (Figure 1); studies from the United States show that chronic pain affects 11 to 38 per cent of children up to 18 years.

A serious health concern, chronic pain can significantly impact a child’s daily functioning, causing difficulties with attending school and engaging in family routines and hobbies. The child’s vital relationships with family, friends and classmates may be affected; they may withdraw from social situations and become more likely to internalise their responses to pain, resulting in mood difficulties or anxiety.

Investigating chronic pain with various causes

Children experiencing chronic pain may not have specific injuries or medical conditions that directly result in their pain. KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH) takes a holistic interdisciplinary approach to help children manage their chronic pain for an optimal quality of life in the long term.

Figure 1. Biopsychosocial Model of Chronic Pain adapted from Gatchel et al., 2007

Image reproduced with permission

The Children’s Pain Management Clinic (CPMC) at KKH facilitates specialist interdisciplinary care for children with chronic pain up to 18 years. The clinic helps young patients learn to manage their pain and resume their daily activities as much as possible, for the long term.

The most common medical diagnoses of child chronic pain seen at CPMC are headaches (including tension headaches and migraines), recurrent or functional abdominal pain, low back pain, neuropathic pain and psychosomatic pain. Other conditions include Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, Iselin’s Disease, and Slipping Rib Syndrome.

Interestingly, there are a handful of these patients who do not report having a previous related injury or medical condition that resulted in pain (such as a fracture or cancer).

Led by an interdisciplinary team comprising a paediatric anaesthesiologist, pain specialty care nurse, occupational therapist, physiotherapist and psychologist, as at 2021, the CPMC sees up to eight new cases a month; a 100 per cent increase from previous years.

Biopsychosocial approach to pain management

Pain education is first provided to help patients and their parents make sense of their pain, decrease dependence on medication and set goals for engaging in activities in spite of pain.

Physiotherapy is also prescribed to help patients relieve muscle tension through stretching and strengthening exercises, and occupational therapy to re-engage with daily activities in a gradual manner. Patients may also be assessed by the paediatric anaesthesiologist to ascertain whether medical treatment is necessary in helping the patient manage their pain during the initial stages of therapy.

Clinical psychologists may be called upon to address psychological factors that may contribute to the child’s chronic pain. These can include dysfunctional thoughts about pain, pain catastrophisation and stressors such as academic stress, peer conflicts and poor family relationships. The clinical psychologist can also help to assess the psychological effects of chronic pain on the child, such as depression and anxiety, and provide evidence-based interventions to manage these conditions.

Age-appropriate psychological interventions are customised to the child’s needs, and can include techniques from Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Mindfulness and various relaxation strategies. Visual aids, such as the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale, and a verbal pain rating scale from zero to 10 are also used to keep track of the child’s pain intensity across treatment sessions.

Within psychology, emotional pain is often expressed as physical pain. Complex psychological issues such as grief, post-traumatic stress disorder and personality disorder traits can contribute to chronic pain. Where necessary, the child may be referred for further assessment by professionals including trauma psychologists, psychiatrists and medical social workers.

Parental involvement key to sustained pain management

Beyond the hospital, continual parental involvement is key to support patients at home and sustain progress made during intervention. Parents can support their children in managing chronic pain by reinforcing pain education, and practising the prescribed relaxation, basic cognitive behavioural therapy and stress management strategies and activity sheets at home.

Useful tips for parents of children with chronic pain:

- Acknowledge your child’s pain as a real experience, and seek timely medical intervention.

- When your child reports experiencing pain, stay calm and direct him/her to the coping strategies taught during the session.

- Provide opportunities for your child to continue their usual daily activities, including doing household chores, going to school, doing homework and going out with friends, with modifications such as reduced duration or taking periodic breaks to rest.

- Encourage your child to participate in daily activities independently and provide physical support only when necessary.

- Provide more attention and praise when your child engages in “pain-free” behaviours and speech.

Case study: Addressing chronic back pain in a school-going teenager through holistic care Sixteen-year-old A experienced a sudden onset of persistent back pain with no known aggravating factors, and was referred to the KKH CPMC. Due to her chronic back pain, A had difficulty carrying out daily activities such as sleeping, getting dressed, taking public transport and attending school. At the CPMC, A was diagnosed with musculoskeletal pain exacerbated by poor sleep, muscle tightness and high academic stress with perfectionistic tendencies. She was provided multidisciplinary intervention focused on addressing the multiple factors that exacerbated her pain. A underwent physiotherapy to help ease muscle tension, and occupational therapy to improve her sleep hygiene and daily activity habits. These included scheduling short-term goals toward long-term goals, taking planned periodic breaks and setting achievable academic goals. She also received psychological intervention to increase awareness of how her pain was linked to stress, and learned to identify stressors and to manage stress and worry. A’s parent participated in psychological sessions to learn how to calmly respond to A when she experienced pain and provide her with opportunities to independently engage in age-appropriate activities. As A experienced frequent pain flares related to peer conflict and examination anxiety, she received further psychological intervention focused on social and emotional communication skills and peer interaction. Medication was only taken when A experienced intense pain flares. A committed to practicing the exercises and skills learnt during her therapy sessions, and her parents were supportive, acknowledged her pain, minimised parental pressure and encouraged her to continue with her daily activities. A year after the initiation of intervention, A could better manage her occasional pain flares despite the challenges of getting used to having new classmates and sitting for examinations. A also reported feeling more confident in engaging with daily activities. After completing her national examinations, A was discharged from CPMC and is currently successfully engaged in daily activities including undertaking a part-time job while waiting to enrol in a university course. |

|

Ms Joanne Ferriol Especkerman, Senior Psychologist, Psychology Service, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital A Senior Psychologist at the KKH Psychology Service, Joanne Ferriol Especkerman specialises in care for children and teenagers, and has been part of the care team at the Children’s Pain Management Clinic for seven years. Joanne has a Master in Clinical Psychology from James Cook University, Australia. She is also a clinical supervisor for clinical psychologists-in-training from National University of Singapore and James Cook University. |

References

- International Association for the Study of Pain. Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Pain 1986;(Suppl 3):S1-S225.

- Gatchel RJ, Peng YB., Peters ML, Fuchs, PN, & Turk DC. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychological Bulletin 2007;133(4):581–624

- King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, MacNevin RC, McGrath PJ, Parker L, MacDonald AJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain 2011;152:2729–38.

- Palermo TM. Impact of recurrent and chronic pain on child and family daily functioning: A critical review of the literature. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 2000;21:58-69.

- Palermo TM, Chambers CT. Parent and family factors in pediatric chronic pain and disability: An integrative approach. Pain 2005;119:1-4.

- Serbic D, Pincus T, Fife-Schaw C, Dawson H. Diagnostic uncertainty, guilt, mood, and disability in back pain. Health Psychology 2016;35:50–9.

- Turk DC, Monarch ES, Biopsychosocial perspective on chronic pain. In: DC Turk, RJ Gatchel, Editors, Psychological Approaches to Pain Management: A Practitioner's Handbook, New York, US: Guilford, 2002.

|