An inherited disorder, Lynch syndrome causes patients to have a lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer (31-38%), endometrial cancer (33%), ovarian cancer (9%) as well as other malignancies2. The condition has an estimated incidence of between 1 in 300 and 1 in 500 in the general population.

Endometrial cancer is particularly prevalent in women with Lynch syndrome, with up to 50 percent of patients presenting with endometrial carcinoma as their first tumour. Previously, patients with Lynch syndrome were identified clinically using validated criteria followed by confirmatory gene testing. However, nearly 70 percent of women with Lynch syndrome presenting with endometrial cancers did not meet the criteria due to an absence of a personal or family history suggestive of the condition3. As such, laboratory-based tests are critical to any Lynch syndrome screening programme3,4.

In February 2017, KK Women's and Children's Hospital (KKH) established a universal Lynch Syndrome Screening Programme for all patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer, regardless of age, in response to a recommendation by the Society of Gynaecologic Oncology to screen for hereditary syndromes5.

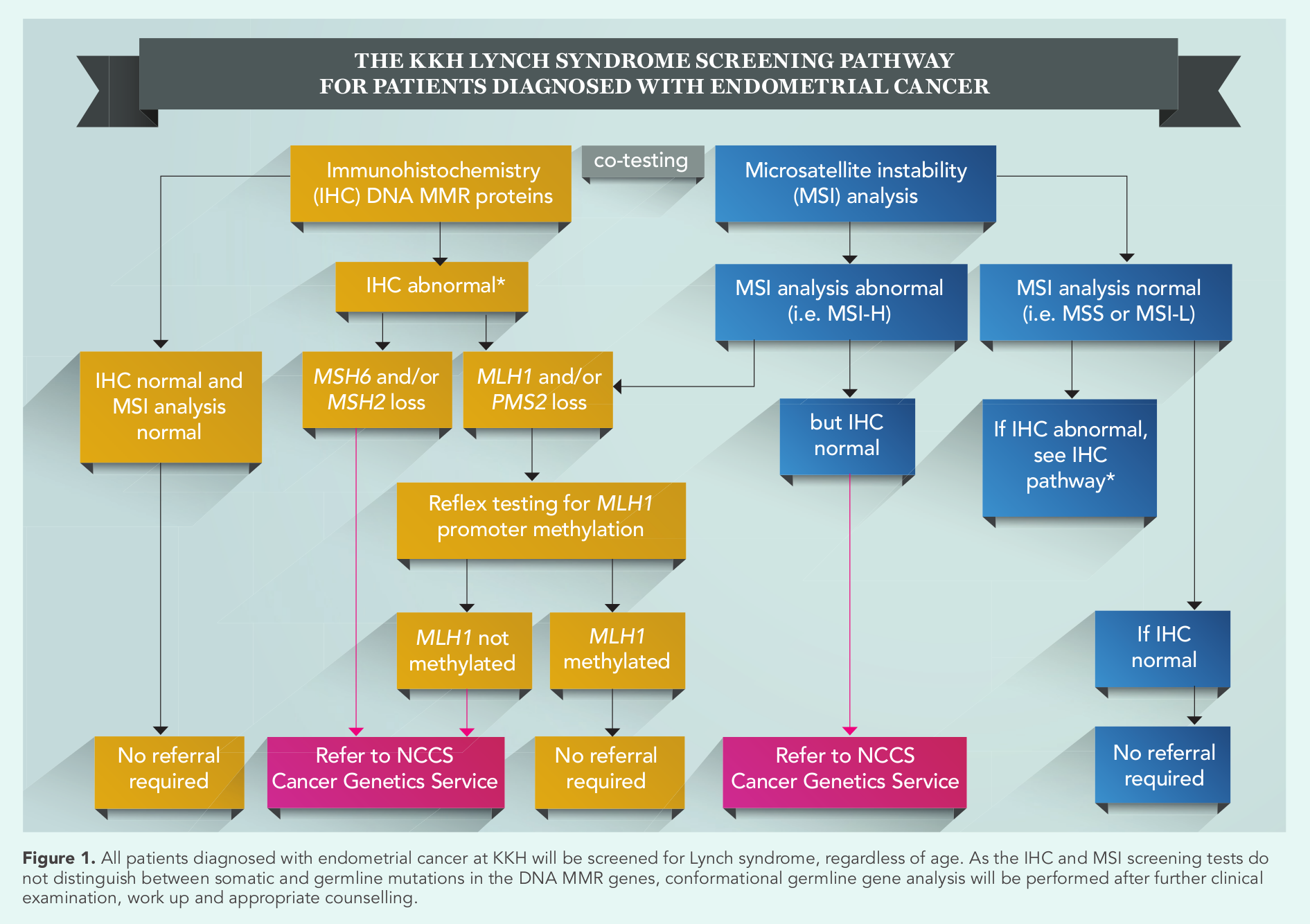

The KKH universal Lynch syndrome screening pathway (Figure 1) comprises laboratory-based immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining and microsatellite instability (MSI) analysis, following which patients with abnormal test results are referred to National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS) for further clinical examination, work up and counselling. Finally, germline gene analysis is performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Identifying the genetic culprit

Also known as hereditary non polyposis colorectal cancer (HPNCC), Lynch syndrome is an autosomal dominant syndrome due to germline mutations in one of the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes (MLH1,

MSH2,

MSH6 and

PMS2), or rarely germline deletions of

EPCAM (resulting in

MSH2 inactivation), causing widespread replication errors/instability in genomic intronic sequences, known as microsatellites, resulting in MSI.

MSI can be caused by either germline or somatic MMR gene mutations. Non-hereditary somatic mutational gene silence through promoter hypermethylation of the

MLH1 gene causes similar MSI levels in the genome seen in 10 to 25 percent of sporadic tumours, especially colorectal and endometrial cancers. Unlike patients with colorectal cancers, further testing for V600E mutation of the

BRAF gene is not beneficial as less than one percent of the population display this mutation.

Germline mutation in the

MSH6 gene is associated with the highest risk for developing endometrial carcinomas. Mutations in

MLH1 result in a higher risk of developing colorectal carcinoma while

PMS2 is associated with the lowest overall risk of developing Lynch syndrome-associated tumors.

The median time for Lynch syndrome patients with endometrial cancer to develop a second tumour is estimated to be 11 years. Therefore, early identification of proband Lynch syndrome patients with endometrial cancer can result in timely and appropriate management to help reduce the potential of a second tumour in the patient, or in the case of her relatives, preventing tumours altogether.

The KKH universal Lynch syndrome screening pathway

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) testing is performed on formalin-fixed-paraffin embedded (FFPE) tumour tissue. The sensitivity and specificity of the four MMR protein markers (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2) are 91 percent and 83 percent respectively; however the test cannot detect germline missense mutations when nonfunctioning MMR protein is produced.

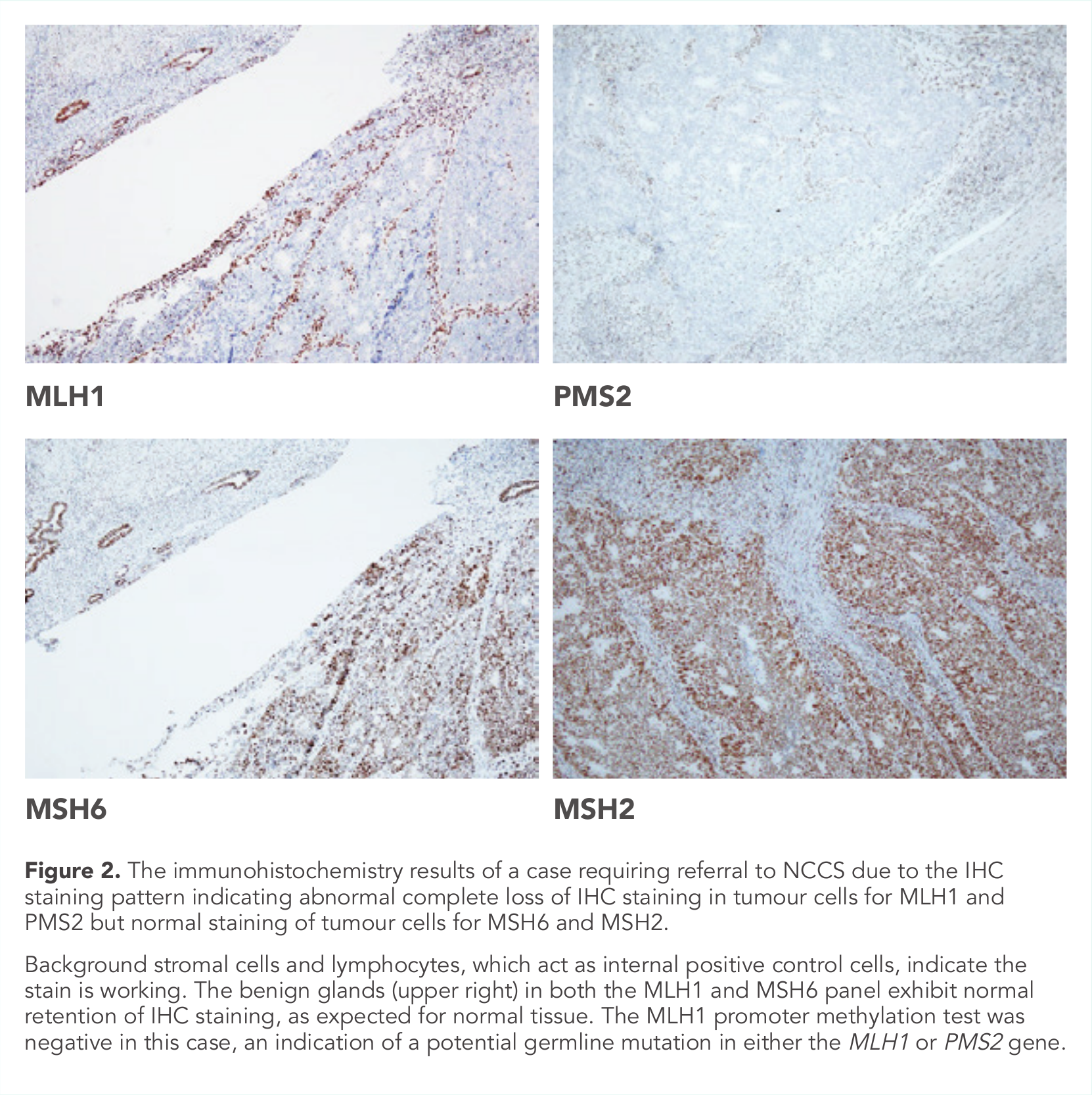

Normal MMR proteins form dimer complexes; MLH1-PMS2 and MSH2-MSH6 pairs. Mutation in one of the genes in the pairing leads to loss of staining of its partner protein (Figure 2). Gene silence via MLH1 promoter methylation causes loss of MLH1/PMS2 IHC staining. Deletions in the EPCAM gene epigenetically silence the

MSH2 gene, resulting loss of MSH2/MSH6 staining.

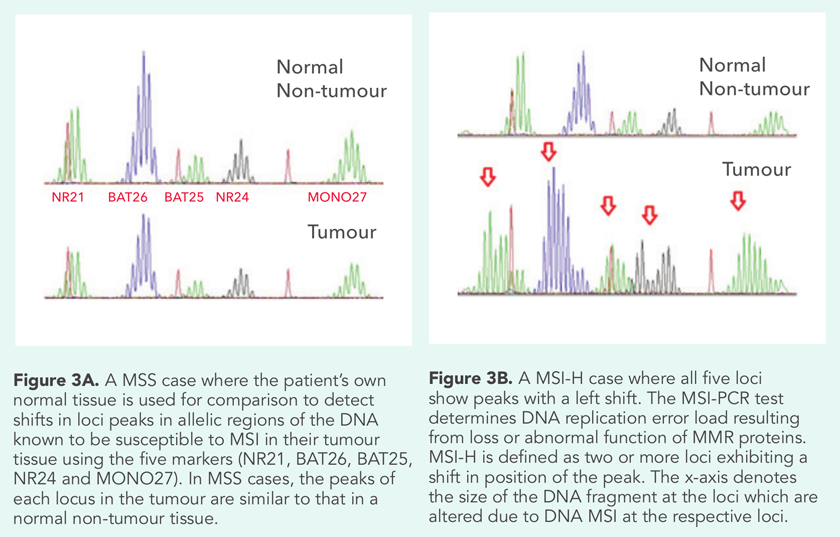

MSI analysis using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is performed on FFPE tissue with a five-marker mononucleotide panel (BAT25, BAT26, NR21, NR24 and NR27). Microsatellite stable (MSS) phenotype tumours will show normal microsatellite repeats as normal tissues. MSI-high (MSI-H) tumours show microsatellite instability in two or more of the tested loci while MSI-low (MSI-L) tumours show instability at one locus (Figure 3). Unlike IHC, MSI PCR cannot identify which gene is mutated.

Tumours with loss of IHC MLH1 protein expression require an additional PCR-based test to detect for MLH1 gene promoter methylation. A patient with a tumour which tests negative with the MLH1 gene promoter methylation test is encouraged to undergo germline mutation testing for Lynch syndrome.

Appropriate counselling and gene sequencing to uncover mutations in

MLH1,

MSH2,

MSH6,

PMS2 and

EPCAM genes are generally performed to confirm suspicions of a germline mutation using the patient’s blood sample.

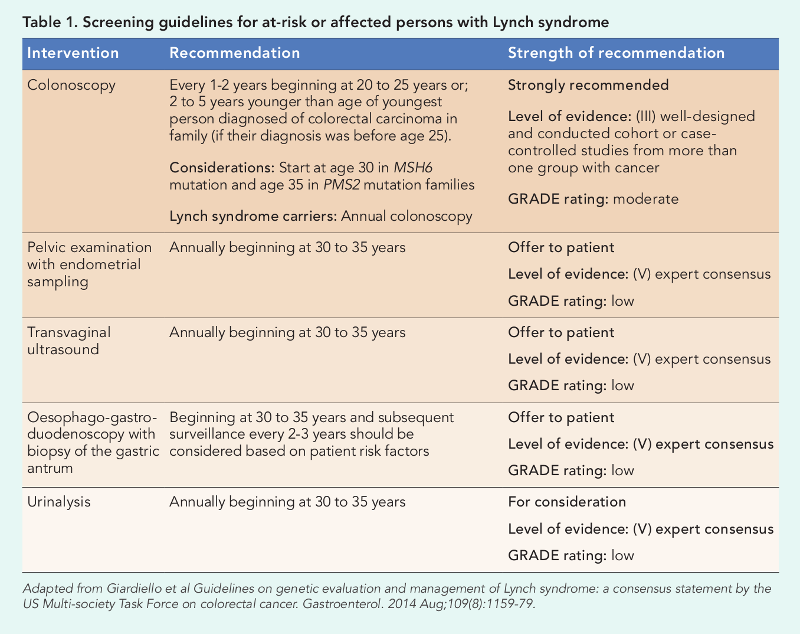

Case study: Managing a hereditary, lifetime risk 57-year-old Madam Tan (not her real name) presented to the Department of Gynaecological Oncology at KKH with postmenopausal bleeding, and was diagnosed with a FIGO grade 2 endometrioid carcinoma with a 60 percent myometrial invasion. She subsequently underwent a total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with staging lymphadenectomy. Post-procedure, in line with the new KKH universal Lynch syndrome screening pathway, IHC and MSI analysis was performed on Madam Tan’s tumour tissue. Laboratory results revealed that the tumour was MSI high, indicating microsatellite instability. Loss of MLH1 and PMS2 MMR proteins – with the MLH1 promoter not methylated – further indicated an MLH1 genetic mutation. Madam Tan underwent chemotherapy at KKH and was concurrently referred to receive genetic counselling at NCCS. She was surprised at her referral, as she was unaware of any family history of cancer, apart from her paternal aunt being diagnosed with colonic adenocarcinoma two decades prior. At NCCS, in-depth history taking by the genetic counsellor enabled a detailed view of the incidence and type of cancers which afflicted Madam Tan’s blood relatives. Through MMR germline gene sequencing, a germline MLH1 pathogenic variant was identified in Madam Tan’s DNA, confirming her diagnosis of Lynch syndrome. Following her diagnosis, Madam Tan was provided with a family notification letter regarding the availability of predictive testing and relevant implications. She later discovered family history consistent with Lynch syndrome involving her paternal grandfather and his two siblings. Her children were diagnosed with the condition as well, and began cancer surveillance, specifically annual colonoscopies. Two years following completion of her chemotherapy, between scheduled surveillance follow-ups (Table 1), Madam Tan visited her community healthcare provider due to constipation. She was referred for a colonoscopy where three tubular adenomas – one with focal high grade dysplasia – were discovered. |

A new paradigm of cancer surveillance

When possible, universal screening to supplement family history reporting is beneficial for the identification of those at risk of Lynch syndrome. Additionally, a multidisciplinary approach to the management of care of these patients and their families is crucial. In the case of Madam Tan, her diagnosis and the establishment of a detailed pedigree of her family tree will help future generations in her family line who are seen at KKH and NCCS to be appropriately counselled about the need to undergo screening for Lynch syndrome, and cancer surveillance if required.

Lynch syndrome screening guidelines

These recommendations are based on the strength of confidence and GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) – a well-accepted rating of evidence relying on expert consensus about whether new research is likely to change the confidence level of recommendations.

|

Dr Adele Wong, Consultant, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital and Adjunct Instructor, Pathology Academic Clinical Program, Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Singapore Dr Adele Wong underwent a fellowship in gynaecologic and breast pathology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA, as part of the SingHealth Health Manpower Development Plan in 2015. Her research interests include gynaecological pathology, in particular endometrial carcinomas. |

|

Ms Eliza Courtney, Genetic Counsellor, Cancer Genetics Service, Division of Medical Oncology, National Cancer Centre Singapore Ms Eliza Courtney delivers genetic counselling services regarding hereditary cancer syndromes to patients with cancer and their families. She holds a Masters of Genetic Counselling from the University of Sydney, Australia, and has previously held genetic counselling positions at a number of tertiary hospitals in Sydney. |

|

Dr Joanne Ngeow, Head, Cancer Genetics Service, National Cancer Centre Singapore and Assistant Professor, Oncology Academic Clinical Program, Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Dr Joanne Ngeow currently leads the Cancer Genetics Service at NCCS with an academic interest in hereditary cancer syndromes and translational clinical cancer genomics. Her current clinical focus and research revolves around understanding cancer predisposition by studying cancers clustering in families, young adults and in families with multiple / rare cancer presentations. |

References: - Giardiello FM, Allen JI, Axilbund JE, Boland CR, Burke CA, Burt RW, et al. Guidelines on genetic evaluation and management of Lynch syndrome: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(2):502-26.

- Bonadona V, Bonaiti B, Olschwang S, Grandjouan S, Huiart L, Longy M, et al. Cancer risks associated with germline mutations in MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6 genes in Lynch syndrome. JAMA. 2011;305(22):2304-10.

- Wong A, Ngeow J. Hereditary Syndromes Manifesting as Endometrial Carcinoma: How Can Pathological Features Aid Risk Assessment? BioMed research international. 2015;2015:219012.

- Goodfellow PJ, Billingsley CC, Lankes HA, Ali S, Cohn DE, Broaddus RJ, et al. Combined Microsatellite Instability, MLH1 Methylation Analysis, and Immunohistochemistry for Lynch Syndrome Screening in Endometrial Cancers From GOG210: An NRG Oncology and Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(36):4301-8.

- Lancaster JM, Powell CB, Chen LM, Richardson DL. Statement on risk assessment for inherited gynecologic cancer predispositions. Gynecol Oncol. 2014.

|