Dr Shiva Sarraf-Yazdi (right) with students she has mentored at Duke-NUS Medical School.

To better prepare medical students for clinical practice in Singapore, Duke-NUS Medical School is revising the curricular ethos, structure and approach. In this piece, Dr Shiva Sarraf-Yazdi, MD, MEHP, Associate Dean, Duke-NUS Office of Education, shares a snapshot of the why and what of recent curriculum changes at Duke-NUS, along with her perspective on the now-what.

The Why

The purpose of the Duke-NUS curriculum revision is to educate high-performing Clinicians First, who also exemplify the School’s ambition to develop Clinicians Plus, with insights and capabilities in science, scholarship, innovation, leadership, and education – to someday contribute to transforming medicine and improving lives. To realise this vision, we aim to better align with the School’s updated Education Mission, upcoming National Outcomes Framework for Medical Graduates, and more importantly, clinical needs of Singapore.

When reality hits home… A few months ago, my husband was hospitalised. Once past A&E proceedings and in his inpatient bed, his first point of contact with a doctor was “Z”, a freshly minted Duke-NUS graduate. Having exchanged greetings, I sat quietly in the corner. With external calm and internal chaos, I did what people lacking control of a situation do: hope for the best. Is my husband in safe hands, I wondered? Had our medical school done enough to shape this young doctor? Was he part of a strong team? Would the “curriculum”, beyond theories and tests, materialize into real-life capabilities?

The What

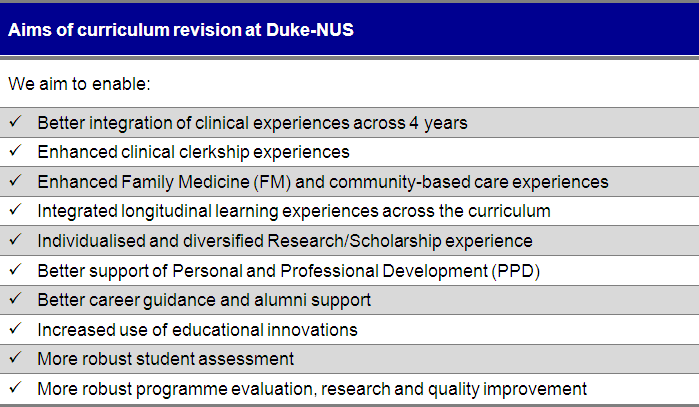

The general curriculum content and learning goals of the MD Programme remain fundamentally unchanged. While details of the 4-year curriculum are beyond the scope of this piece, the overarching aims of our curriculum revisions are shared in the below table. This tabulation reflects the efforts and engagement of countless students, staff, alumni, and faculty collaborating to bring the changes to fruition.

Embarking on curricular revisions necessitates an ongoing study of the literature. Such reviews interestingly reveal countless calls for medical education reform over time. This makes me wonder where our changes stand.

“Back in my day”. Along with scientific advances, changing values and cultural norms have shaped expectations of the medical profession. Hodges portrays a doctor of the late 1800s as one in “a three-piece suit and a walking stick with a silver head”1, exemplifying an intimate tie between clinical competence and appearances. Fast-forward to late 1900s and my own medical student days. Though not as dapper, we would not be caught (dead) in the wards wearing scrubs. Nowadays, it is the accepted professional norm for our students to walk around in scrubs (sigh!). Beyond (d)evolving wardrobes, each generation presumes that it faces entirely novel issues with which to grapple.

“This time is different”. Despite evolving changes in healthcare, the essence of calls for education reform have interestingly changed little.2 Whitehead et al. identifies a pattern akin to circling “carousel ponies”, many themes re-emerging and repackaged as new and urgent issues of their time.2 Take for example, the “need for generalism”, given that a “definite trend in medicine during the past fifty years” has been “that of specialization”2. Is it surprising that this comes from a 1950 article? How about prioritizing “maintenance and preventive health”, addressing “growth of biomedical knowledge and technology”, focusing on “preventive and public health”, and broadening student selection to include “well balanced” personalities?3 These age-old themes could have easily been plucked from a list of present-day health priorities. Could it be that we, too, are merrily fueling the “circling ponies” (and who doesn’t like ponies)?

The Now What

If we learn one lesson from history, is it that we rarely learn from history?

What goes around, may come around. Underlying time-honored practices are myriad assumptions, biases and beliefs. We call for focus on community care, yet perpetuate historical and political practices that feature several months of say, inpatient surgery, and only short stints dedicated to mental health. We assume longer brew time is automatically better, overlooking whether time-based education is fundamentally grounded on logistical concerns, or logical considerations. We deem one arbitrary assumption “better” than the next, tweak and tinker with changes, and posit “this time is different”.

If we rarely learn from history (my assumption!), we could at a minimum espouse education tenets that have withstood the test of time. Though not easy, some steps are simple. To be fully effective, graduate entry students should not be passive observers, but active participants in immersive and safe care of patients.1, 4 We can foster habits of inquiry and improvement of care, uncovering assumptions, and embracing professionals who themselves strive to advance health.1 We can cultivate an environment conducive to learning, and importantly, show zero tolerance for voices and behaviours that imperil its safety for learners.

Contextual influences in the clinical environment can profoundly undermine a learner’s views, values, and place within the profession. Years of formal training and acquiring patient-centred skills can be readily jeopardized when we do not model such behaviours.4 We can support students’ professional identity development, if we foremost hold ourselves accountable to the highest standards of professionalism. Then, we can and should, hold our young colleagues accountable to the highest of standards.1 These tenets, rehashed from over 100 years ago1 are relevant still. Yet, one can always improve.

From circling around, to breaking new ground. Making an impactful dent in our approach to medical education, rather than coming from a medical school in a silo, necessitates the activities of the whole community of learning. With no shortage of dedicated and determined colleagues from all walks of life, the SingHealth Duke-NUS partnership is in a unique position to hop off the merry-go-round of calls. It can even one day lead health professionals’ education beyond its borders, supported by capable, transparent and participative leadership open to challenging the status quo, as a collective ambition.

In the meantime, can we be actively building connections, creating open opportunities for shared reflection, and ultimately moving past the strong clinical partnership, toward (selectively) collective ownership of our community of learning? Would this time be different, if our students recall their “back in my day” as a community that amidst many changes and challenges, was relentlessly pursuing, modeling, and expecting an aspirational goal of excellence – “striven for but never achieved, as one can always improve”1?

Thankfully… my husband made it out of the hospital, better. And young Dr Z did not disappoint. He was poised, proficient and professional at every turn. At his level, he couldn’t have done any better. Even back in my day.

Let’s connect! I welcome dialogue over a coffee chat, reserving the right to pontificate on things “back in my day”: [email protected]

References

1. Irby D, Cooke M, O’Brien C. Calls for reform of medical education by the Carnegie foundation for the advancement of teaching: 1910 and 2010. Acad Med. 2010 Feb; 85: 220-7.

2. Whitehead C, Hodges B, Austin Z. Captive on a carousel: discourses of ‘new’ in medical education 1910–2010. Adv in Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2013; 18: 755–68.

3. Hodges B. The shifting discourse of competence. In Hodges BD, Lingard L, editors. The question of competence: Reconsidering medical education in the twenty-first century. Ithaca, NY: ILP Press of Cornell University Press; 2012.

4. Hodges B, Kuper A. Theory and Practice in the Design and Conduct of Graduate Medical Education. Acad Med. 2012; 87: 25-33.