Research into nutrition has traditionally focused on the quantity and quality of food ingested, linking portion size, energy and nutrient composition with metabolic outcomes. However, there is mounting evidence that the time profile of food intake is metabolically relevant above and beyond food portion and composition. The timing of when we eat has been documented as an important determinant of circadian rhythms in metabolic pathways.

In animal models, nocturnal rodents given eight to 12 hours of food access during their active phase (i.e. night-time) had improved oscillations of circadian clock components in the liver and glucose tolerance, compared to rodents fed under an ad libitum regimen. In clinical trials among the adult human population, enhanced weight loss and improved glycaemic control were found in those with lower caloric intake in the evening than morning, despite similar total caloric intake for the entire day.

On the basis of these studies, it was concluded that predominantly night-time caloric intake could negatively impact glucose and metabolic regulations. To date, this area remains largely unknown among pregnant women, a high-risk population vulnerable to gestational hyperglycaemia; as well as among young children, where early childhood serves as a critical window for obesity and metabolic disease prevention.

A better understanding of how the timing of food intake, fasting intervals and eating episodes relates to plasma glucose concentrations in pregnant women and weight status in young children may lead to improved strategies in managing metabolic health among these target populations.

Close links between maternal and child food timing, and metabolic health

Leveraging Singapore’s ideal conditions for conducting circadian-related studies, where sunlight exposure occurs at a fairly constant length of 12 hours daily throughout the year (i.e. sunrise is approximately at 7.00am and sunset is approximately at 7.00pm), we conducted several studies examining the daytime and night-time food intake of pregnant women and 12-month-old infants.

We studied the time profile of food intake from the aspects of day-night caloric intake, fasting intervals and eating episodes – looking for associations with plasma glucose concentrations and weight status, respectively.

Data from Growing Up in Singapore Towards healthy Outcomes (GUSTO), a large scale mother-offspring cohort study, was used and the studies were led by Dr Loy See Ling, Research Fellow, Department of Reproductive Medicine;

Associate Professor Fabian Yap, Head and Senior Consultant, Endocrinology Service; and

Associate Professor Jerry Chan, Senior Consultant, Department of Reproductive Medicine, from KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital.

Implications of predominantly night-time caloric intake for pregnant women

Among 985 pregnant women, it was found that 15 per cent consumed 50 per cent more calories during night-time (from 7.00pm to 6.59am) than daytime (from 7.00am to 6.59pm) at 24 to 28 weeks’ gestation1. Pregnant women with a greater night-time caloric intake had higher levels of fasting plasma glucose during the late second trimester1.

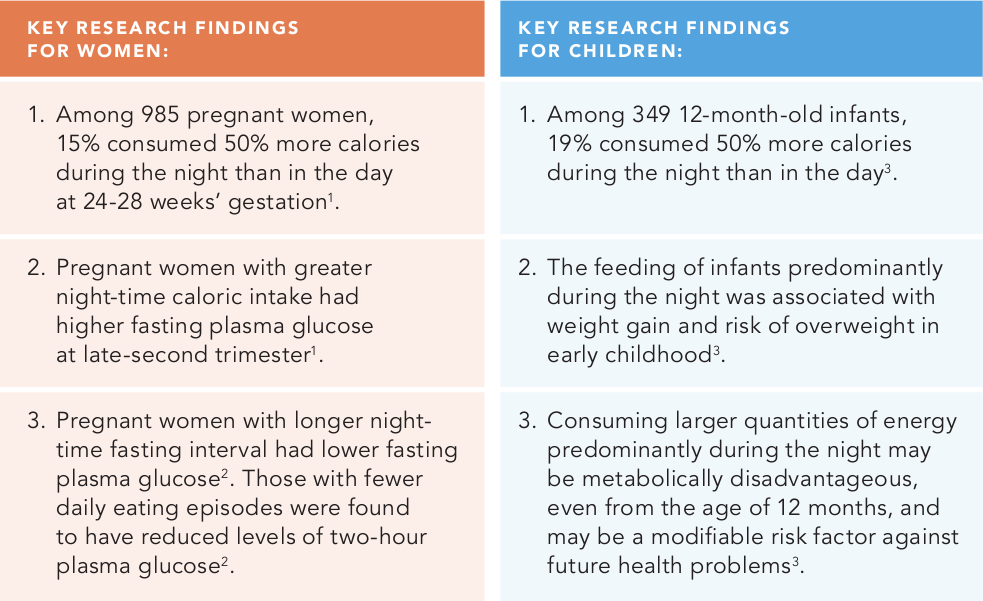

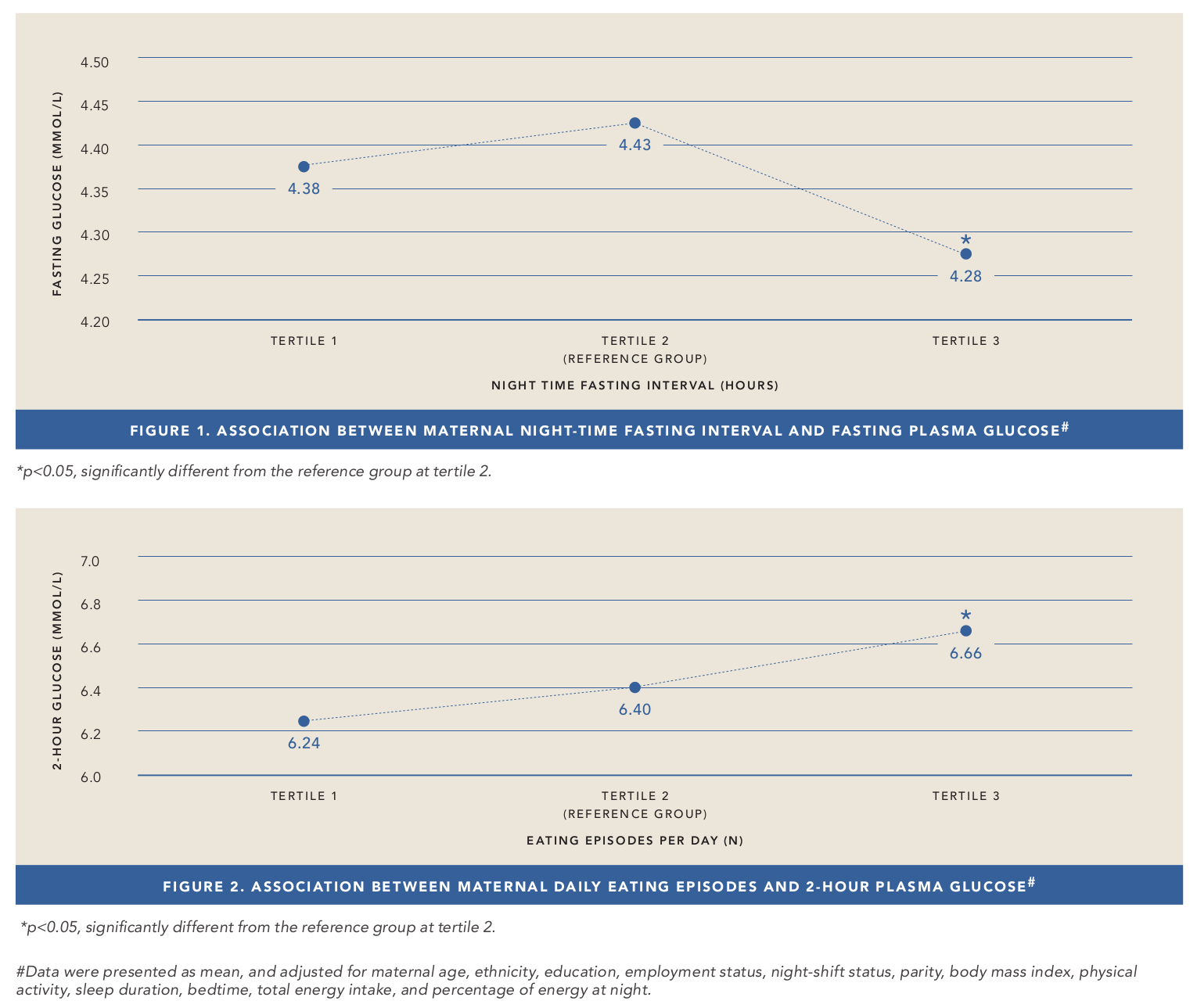

It was subsequently demonstrated that pregnant women with longer night-time fasting intervals had lower levels of fasting plasma glucose (Figure 1)2. Furthermore, pregnant women with fewer daily eating episodes were found to have reduced levels of two-hour plasma glucose (Figure 2)2.

While these changes in glycaemic levels in response to food timing may seem inconsequential, however, over time, they may have a significant effect to aid prevention of gestational hyperglycaemia and its consequences for the mother/offspring in view that the risks of adverse perinatal outcomes can occur, which increase continuously in association with rising maternal glucose levels.

Gestational hyperglycaemia contributes to adverse perinatal outcomes, neonatal adiposity and long-term risk of obesity in offspring. These occur throughout the range of glycaemia, even at concentrations below the diagnostic cut-off for gestational diabetes mellitus. Evidence suggests that even modest glycaemic improvement in pregnant women with mild glucose intolerance improves perinatal outcomes2.

Implications of predominantly night-time caloric intake for infants

At 12 months, an infant’s daily sleep/wake cycle is moderately stabilised with an increasing consolidation of sleep during the night compared with early infancy, implying that consistent and stable daily feeding practices may be in place. Hence, infant feeding practices at 12 months deserve more attention, as this is a transition period that is critical in setting the foundation for food choices and eating habits later in life.

Among 349 12-month-old infants, it was found that 19 per cent were predominantly night-time feeders – consuming 50 per cent more calories during the night (from 7.00pm to 6.59am) than in the day (from 7.00am to 6.59pm). These infants had a larger weight gain from 12 to 24 months and higher risk of becoming overweight at 24 months than infants who were predominantly fed during daytime hours.

These findings suggest that consuming larger quantities of energy predominantly during the night-time may be metabolically disadvantageous, even from the age of 12 months, and may be a modifiable risk factor against future health problems3.

Influencing food timing to improve health outcomes

These findings raise the possibility of including advice for pregnant women and caregivers of young children on adopting time-based eating patterns to improve their long-term metabolic health. Benefits for pregnant women can include enhanced glucose level control and a lower risk of gestational hyperglycaemia.

Benefits for young children can include the establishment of feeding behaviours that may habituate the child to maintain similar eating patterns in adulthood – making early childhood a potentially critical window for obesity prevention.

These findings may also be valuable to inform the custom of night-time eating that is commonly practised in modern society, towards bettering public health.

To confirm our findings and evaluate the clinical practice applicability, more long-term and large-scale randomised trials are warranted.

Preliminary findings from observational studies are promising, and work is ongoing to analyse long-term weight outcomes for young children in relation to their day-night feeding patterns.

These studies are supported by the Singapore National Research Foundation under its Translational and Clinical Research (TCR) Flagship Programme and administered by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council (NMRC), Singapore (NMRC/TCR/004- NUS/2008; NMRC/TCR/012-NUHS/2014).

Additional funding is provided by the Singapore Institute for Clinical Sciences, Agency for Science Technology and Research (A*STAR), Singapore.

|

Dr Loy See Ling, Research Fellow, Department of Reproductive Medicine, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital Dr Loy See Ling completed her Bachelor of Science (Dietetics) and Doctor of Philosophy (Human Nutrition) in Malaysia. She is currently conducting research related to maternal and child health by engaging in preconception and pregnancy prospective cohort studies in Singapore – namely the ‘Growing Up in Singapore Towards healthy Outcomes’ (GUSTO) study and ‘Singapore PREconception Study of long-Term maternal and child Outcomes’ (S-PRESTO) study. Dr Loy has a special interest in early nutrition and its effects on later health, in particular obesity and diabetes. |

References: - Loy SL,* Cheng TS,* Colega MT, Cheung YB, Godfrey KM, Gluckman PD, Kwek K, Saw SM, Chong YS, Natarajan P, Muller-Riemenschneider F, Lek N, Yap F, Chong MFF, Chan JKY. Predominantly night-time feeding and maternal glycaemic levels during pregnancy. British Journal of Nutrition. 2016; 115: 1563-1570. IF 3.302.

*co-first author - Loy SL, Chan JKY, Wee PH, Colega MT, Cheung YB, Godfrey KM, Kwek K, Saw SM, Chong YS, Natarajan P, Muller-Riemenschneider F, Lek N, Chong MFF, Yap F. Maternal Circadian Eating Time and Frequency Are Associated with Blood Glucose Concentrations during Pregnancy. Journal of Nutrition. 2017; 147:70-77. IF 3.74.

- Cheng TS,* Loy SL,* Toh JY, Cheung YB, Chan JK, Godfrey KM, Gluckman PD, Saw SM, Chong YS, Lee YS, Lek N, Chong MFF, Yap F. Predominantly nighttime feeding and weight outcomes in infants. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2016; 104: 380-388. IF 6.770. *co-first author

|