KEY POINTS

|

- Children who somatise, experience and communicate psychological distress through physical symptoms. This may lead to repeated visits to the doctor or emergency department.

- Majority seen at KKH are female and secondary school-aged.

- Abdominal pain is the most common presenting complaint, followed closely by chest pain and headaches (Figure 1).

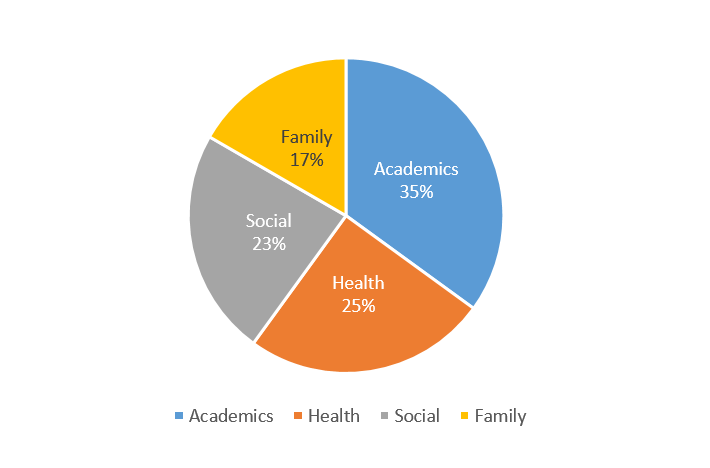

- Academic / school-related issues are the most reported stressors (Figure 2).

|

Clinical presentation

Psychosomatic symptoms in children and adolescents typically present as physical discomforts such as stomachaches, chest pains and headaches. They can occur as a result of stress and may or may not be associated with a medical condition.

In some situations, the symptoms may point toward a medical diagnosis, but the frequency, nature and intensity of the symptoms are not in keeping with the existing diagnosis. Another term which is sometimes used is “medically unexplained symptoms”. A crucial point is, although the medical investigations may not provide an explanation for the symptoms, they are real to the person who is experiencing them and are not a figment of their imagination.

- Psychosomatic (somatic) symptoms are persistent physical symptoms which may or may not be associated with a medical diagnosis. These can include stomachaches, chest pains and headaches.

- While medically unexplained, the physical symptoms are real to the person, not a figment of their imagination.

|

Somatic symptoms are like a fire alarm but without the smoke and fire. Usually, these symptoms may signal disease or bodily distress, but oftentimes they could be the result of false signalling in the nervous system. Sometimes, it is not easy to turn off this signal. Imagine how distressing it must be to keep hearing the fire alarm and running for safety, only to find out you were never really in danger.

“Somatic symptoms are like a fire alarm but without the smoke and fire…

Imagine how distressing it must be to keep hearing the fire alarm

and running for safety, only to find out you were never really in danger.” |

Epidemiology

Somatic Symptom Disorder is the newest term used in the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), and research in this area confirms that psychosomatic symptoms are common. A 2017 study in a tertiary level paediatric emergency department found that nearly nine per cent of children who complained of pain met the diagnostic criteria for Somatic Symptom Disorder.1

Another significant finding is that between one third to one half of children who present with somatic symptoms are found to have other psychopathology, including emotional difficulties such as anxiety or depression.2,3

Why is it important to intervene?

Psychosomatic symptoms are very real, and psychological and physical symptoms can be closely interconnected. Persons who somatise, experience and communicate psychological distress through physical symptoms. These can lead to multiple help-seeking behaviours; they often present repeatedly to the primary care doctor, paediatrician or emergency department.

Children with psychosomatic symptoms who present to healthcare facilities may receive medical attention, but not necessarily the psychological intervention that they need to feel better. This is a key reason why we need to have services which can address both physical and mental health issues.

The biopsychosocial framework is the recommended assessment and management model. In this model, problems are not regarded as either physical or mental, but take into account the contribution from biological, psychological and social factors. Optimum outcomes are seen when healthcare disciplines and families work collaboratively.

Brief and timely hospital-based assessment and intervention

The RECAP (REsilience in Children and Adolescents with Psychosomatic symptoms) programme at KKH utilises a stepped care model to provide brief and timely outpatient assessment and intervention for children aged five to 18 years. A RECAP-Lite programme consisting of three sessions is offered to patients with milder symptoms of less than six months’ duration, administered by advanced practice nurses, medical social workers or school counsellors.

The RECAP programme is offered to patients with moderate symptoms of six to 12 months’ duration, administered by clinical counsellors and psychiatrists. Patients with severe somatic symptoms are referred to the KKH Psychology Service for support.

The aims of the programme are to reduce the distress of children and their caregivers, and increase functioning and quality of life. It focuses on educating both parent and child on the mind-body connection; increase emotional self-awareness, expression and regulation; improve coping skills and teach relaxation strategies. Caregiver participation is essential to empower parents to support their child on their journey of recovery.

- Educate the parent and child on the mind-body connection, emotional self-awareness, expression and regulation, coping skills and relaxation strategies, as well as parental roles in caring for a child who experiences and communicates psychological distress through physical symptoms.

|

Between October 2020 and June 2022, the profile of RECAP beneficiaries was 72 per cent female, 63 per cent of secondary school age – the age where children tend to experience life significant transitions such as the Primary School Leaving Examinations (PSLE). Abdominal pain was the most common presenting complaint, followed closely by chest pain and headaches (Figure 1). Academic / school-related issues were the most reported stressors (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Presenting complaints

Figure 2. Reported stressors

What can the healthcare professional do to help?

When told by doctors that the child’s pain is likely psychological, parents and children may get entrenched into the idea that the pain must be either mental or physical. The assessment process by the healthcare professional can have therapeutic benefits:

-

Reassure that the pain is real and that there are evidence-based ways to manage the psychosomatic symptoms. This can be validating for the child and reassures parents that there is more that they can do for their child.

-

Build a blame-free narrative by helping parents and their child develop a good understanding of the mind-body connection (Watch a video about the mind-body connection here).

-

Validate and address any confusion, frustration and anxiety they may have experienced through the journey of somatisation of the child.

-

Encourage parents and children who may still feel unsure about treating somatisation with psychological interventions. They can also be encouraged to continue to engage with medical assessments to rule out organic issues.

Healthcare professionals can refer a child to the

KKH Psychology Service for tertiary assessment for psychosomatic symptoms, at

+65 6692 2984 or

[email protected].

Resources:

|

|

Dr Shirley Pat Fong, Consultant, Child & Adolescent Mental Wellness Service, Department of Psychological Medicine, KK Women's and Children's Hospital

Dr Shirley Pat Fong received her medical degree from Trinity College, University of Dublin, Republic of Ireland. She worked in paediatrics before training in psychiatry and completing specialist training in child and adolescent psychiatry in London, United Kingdom. Dr Fong’s research interests include neurodevelopmental psychiatry and psychosomatic disorders.

|

|

Ms Liyana Gatot, Senior Clinical Counsellor, Mental Wellness Service, Department of Psychological Medicine, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital

Liyana is a Registered Counsellor (CMSAC) and has worked in counselling with children, adolescents and families since graduating from Monash University with a degree in Psychology. She is currently a clinical supervisor in the niche of psychosomatic disorders as well as paediatrics and women’s mental health.

|

References

- Cozzi G, Minute M, Skabar A, Pirrone A et al.(2017), Somatic symptom disorder was common in children and adolescents attending an emergency department complaining of pain. Acta Paediatr 106(4):586-93

- Campo JV, Bridge J, Ehmann M et al(2004), Recurrent abdominal pain, anxiety, and depression in primary care. Paediatrics, 113, 817-824

- Dorn, Lorah D, Campo, John C, Thato, Sathja et al(2003), Psychological comorbidity and stress reactivity in children and adolescents with recurrent abdominal pain and anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42(1): 66-75

|