Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has established an inimitable role in the management of patients with severe coronary artery disease.

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has established an inimitable role in the management of patients with severe coronary artery disease.

By Asst Prof Chin Chee Yang, Senior Consultant, Department of Cardiology

Since its inception in the late 1970s as a “simple” balloon-catheter method, the technique has evolved into a highly sophisticated procedure. It now incorporates implantable drug-eluting stents, specialised guidewires, plaque-modifying devices, and more.

Arguably, the most significant change in PCI technique worldwide over the last five to ten years has been the wider adoption of intravascular imaging (IVI) as a routine part of the PCI procedure. The limitations of coronary angiography are well recognised. Essentially, angiography assesses only the arterial lumen, providing little or no information about the type of plaque causing a stenosis, its volume, or its distribution. Moreover, angiography lacks the fidelity to reliably identify PCI complications such as stent malapposition and stent edge dissection.

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), conceived in the 1980s, uses a miniaturised ultrasound probe mounted on a catheter to provide a 360-degree cross-sectional view of the vessel from within1. This innovation allowed physicians to visualise plaque types in vivo, enhancing the understanding of coronary artery disease pathophysiology. It led to the identification of plaque features associated with future cardiac events, now commonly known as “vulnerable plaque”. IVUS also improved comprehension of the PCI procedure, revealing dissections and recoil after balloon angioplasty, and guiding optimisation of stent implantation.

The Clinical Impact: Evidence Supporting IVI-Guided PCI

The use of IVUS influenced the PCI procedure in several ways. Operators were more inclined to use larger diameter stents and balloons when their procedures were guided by IVI versus angiography alone, thus achieving greater final lumen areas during PCI. This indicated a tendency to under-size vessels using angiography, and an increased confidence amongst operators to upsize their devices with IVI guidance. In these early non-randomised data, IVI guidance was also associated with a reduction in important adverse patient events such as stent thrombosis, in-stent restenosis, and myocardial infarction.

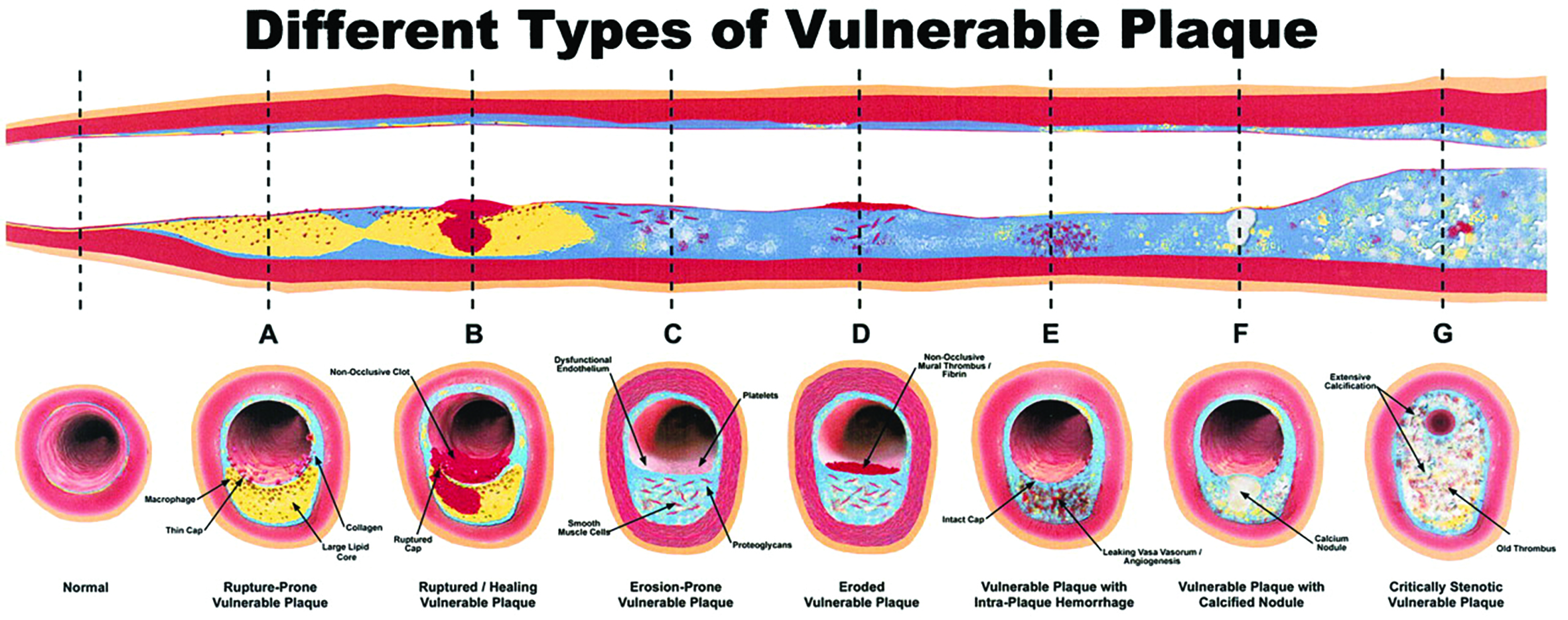

Significant amount of plaque may develop within the coronary artery (A-F) before the lumen calibre is compromised (G). Angiography alone is only able to identify luminal stenosis whereas intravascular imaging allows a better understanding and assessment of plaque composition and distribution.

[Source: Naghavi M, et al. Circulation 2003; 108:1664-1672]

The uptick in IVI use over the last five to ten years has coincided with a stagnation in stent technology. As attention turned to other aspects of PCI, more dedicated IVI trials were initiated, including the first large multi-centre randomised controlled trials (RCTs). The IVUS-XPL2 and ULTIMATE3 trials were among the first large RCTs in IVI. Both found that IVUS-guided PCI was associated with improved patient outcomes, especially target vessel revascularisation, up to five years post-procedure. The magnitude of reduction in adverse patient events was particularly impressive, with a relative reduction of approximately 45% when using IVUS guidance over angiographic guidance alone. These consistent positive trial findings have led to the recent 1A (highest possible) recommendation in the European Society of Cardiology guidelines that intravascular imaging should be performed in patients with complex anatomy undergoing PCI.

A Closer Look: IVI Technologies and Their Considerations

Several intravascular imaging modalities exist. Generally, they comprise a transducer mounted on a thin catheter, typically less than 2mm in diameter. The catheter is advanced over a coronary guidewire into the coronary artery beyond the lesion of interest. When activated, the imaging transducer emits electromagnetic waves in a 360-degree arc, which are reflected off the vessel wall to varying extents according to the plaque properties. These reflections are translated into a cross sectional image of the vessel, allowing differentiation of structures and plaque types. The imaging catheter is usually then pulled back along the vessel to allow a longitudinal assessment.

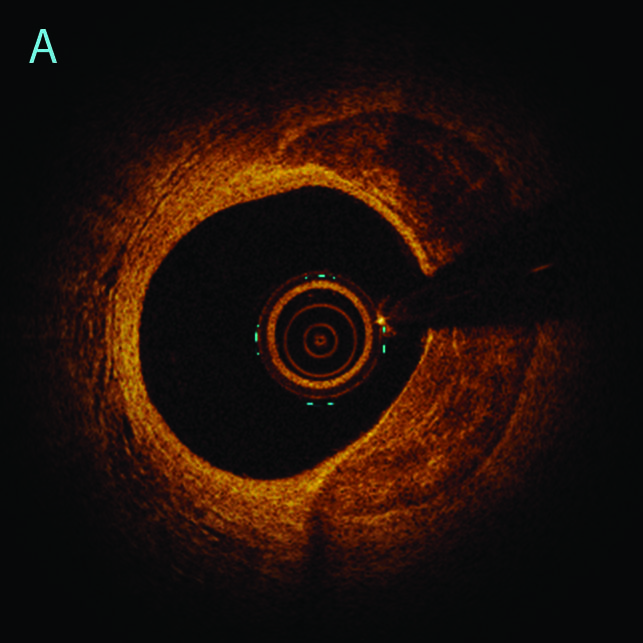

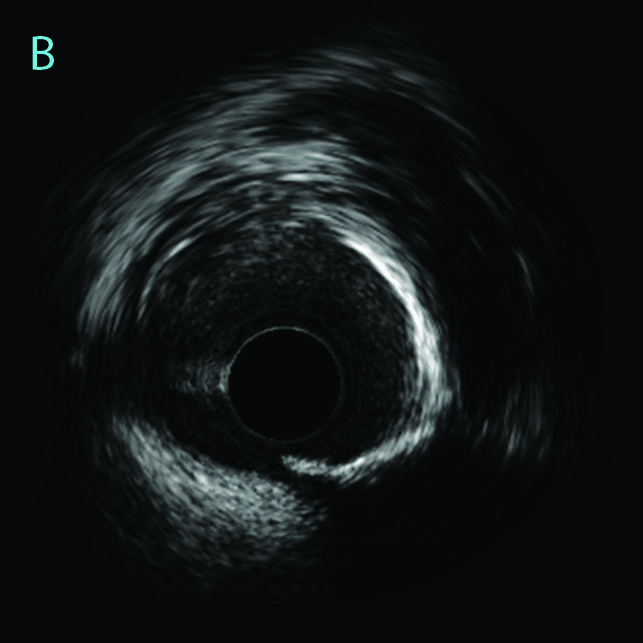

An example of an optical coherence tomography (A) and an intravascular ultrasound (B) image of eccentric calcific plaque in the distribution of 12 to 6 o’clock. Different intravascular imaging modalities have different properties and produce varying images according to plaque type.IVUS utilises a transducer that emits ultrasound waves. The major advantages of IVUS are its ease of use, good tissue penetration and already widespread adoption with a large evidence base. Optical coherence tomography (OCT), developed after IVUS, uses light waves to produce images. OCT’s primary advantage is its extremely high-resolution images, which reduce interpretation ambiguity and allow for more reliable automated software assessments. The main disadvantage of OCT is its requirement for blood clearance from the lumen, which commonly necessitates additional contrast injections. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) provides both qualitative and quantitative measures of lipid-rich plaque burden, allowing for an objective measure of plaque vulnerability. Combination catheters of NIRS+IVUS and OCT+IVUS are also in the market, although their use remains limited.

It is worth noting the limitations of IVI. The procedure requires inserting a coronary guidewire and an imaging catheter into the coronary artery, which carries inherent risks of complications. The additional cost of an imaging catheter must also be factored in, on top of the already substantial cost of PCI. Importantly, IVI is not a treatment but an adjunctive tool in the PCI procedure. Its effectiveness relies heavily on the operator’s interpretation and subsequent actions to optimise the PCI result. Therefore, thorough training and practice are crucial.

Intravascular imaging has transformed from being a novel research tool to an almost basic requirement for all contemporary cardiac catheterisation laboratories, becoming an integral part of modern PCI practice. It continues to develop rapidly, and as further refinements are made, we can expect to see improvements in safety, performance, and hopefully affordability.

REFERENCES

1. Yock P. Intravascular Ultrasound Looking Below the Surface of Vascular Disease. Circulation. 1990 May;81(5):1715:18).

2. Hong S et al. Effect of Intravascular Ultrasound–Guided Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation: 5-Year Follow-Up of the IVUS-XPL Randomized Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020 Jan 13;13(1):62-71.

3. Gao X et al. 3-Year Outcomes of the ULTIMATE Trial Comparing Intravascular Ultrasound Versus Angiography-Guided Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021 Feb 8;14(3):247-257.

Last line: This article is from Murmurs Issue 48. Click here to read other articles or issues.