SGH performs Southeast Asia’s first blood-group-incompatible living-donor liver transplant.

SGH performs Southeast Asia’s first blood-group-incompatible living-donor liver transplant

By Denyse Yeo

A son, no matter how loving or willing, usually can’t give a portion of his healthy liver to his ailing father if their blood groups don’t match. This is because the latter’s immune system will mount an attack on the donated organ, perceiving it as foreign and a danger.

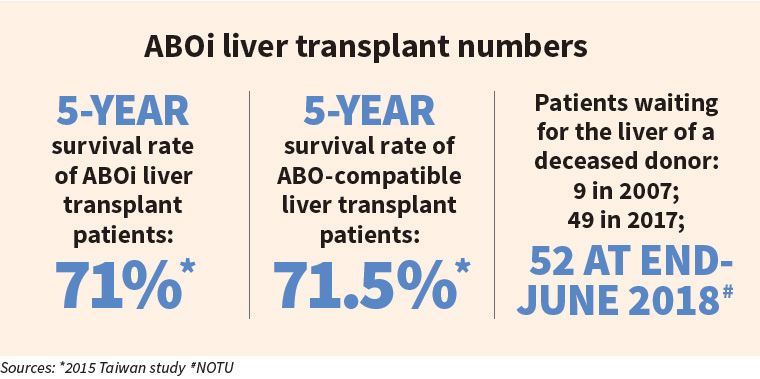

But a new Singapore General Hospital (SGH) treatment protocol has allowed a father-and-son pair to undergo a blood-group-incompatible or ABOi liver transplant. The success of the landmark transplant – it is the first in Southeast Asia – means that those needing a liver transplant urgently now have a greater chance of finding a potential donor.

“Typically, the blood group of the donor and recipient must match for liver transplant,” said Associate Professor Jeyaraj Prema Raj, Director, Liver Transplant Programme, SGH, and Head, SingHealth Duke-NUS Liver Transplant Centre.

“With this treatment protocol, ABOi liver transplant may be possible between some recipients and living donors. Both must undergo stringent tests prior to surgery and regular medical follow-up with their doctor post-transplant.”

The SGH liver transplant team used a treatment protocol adapted from transplant centres overseas after studying how it was done in places like Japan and South Korea. The treatment involves only removing the ABOi-blood-group-specific antibodies, he said.

The team also drew on the experience of the SGH kidney transplant team, which has been performing ABOi living-donor kidney transplant and tissue-incompatible transplant since 2009 and 2013 respectively.

“The treatment allowed us to ‘reprogramme’ the human body to accept an ABOi graft , which had not been possible before. Because this was the first case, we had to get it right. Failure would have meant re-transplant or death. But we were confident because this has been done overseas many times,” said Prof Prema Raj, noting that 50 per cent of living liver- transplant donors in Japan and South Korea are ABOi.

The SGH team performed the first ABOi living-donor liver transplant in July 2017. Mr Chen Qingzhong, 32, donated part of his liver to his father, Mr Chen Yu Hui, 56, in a 12-hour operation. The son’s blood group is A+ while the father’s is B+.

A son’s sacrifice

The elder Mr Chen suffered from liver cancer, hepatitis B and liver cirrhosis. Without a liver transplant, he would have had less than two years to live. He was not eligible to receive a liver from a deceased donor because there was a high chance his cancer could recur. Organs from dead donors are prioritised for liver cancer patients whose illness is least likely to recur.

The younger Mr Chen offered his liver to try and save his father’s life. “The pain from the operation was not as much as not giving Dad a second chance. The physical pain can be overcome,” he said.

To ensure that nothing would go wrong, the team prepped relentlessly. A large multidisciplinary team that included medical and allied health professionals, as well as blood support from the Health Sciences Authority and SGH Blood Bank, was involved.

To prepare for the transplant, the SGH team gave Mr Chen Yu Hui the drug rituximab to suppress production of antibodies in his blood. The drug is normally used to treat some autoimmune diseases and cancer. He was also put on a special dialysis machine to reduce the antibodies already present in his blood to a level low enough for the transplant.

Two weeks after the transplant, the elder Mr Chen went through another round of dialysis. The level of antibodies in his blood was also measured every day to ensure it remained low.

Both men recovered well and continue to receive follow-up medical checks. The younger Mr Chen even became a new father in November 2017. He had 60 per cent of his liver taken out for transplant, but within six weeks of the procedure, his liver grew back to 100 per cent, said Prof Prema Raj.

As with other people who have received a donor organ, the elder Mr Chen will be on immunosuppresants for life. But one year after his transplant, Mr Chen is down to taking just one drug of low dosage, said Prof Prema Raj.

THIS ARTICLE WAS FIRST PUBLISHED IN SINGAPORE HEALTH JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019.