The Blended Longitudinal Integrated Clerkship at Duke-NUS allows for an alternative path to induct medical students into clinical practice.

From hectic schedules to critical reflections, the blended Longitudinal Integrated Clerkship at Duke-NUS allows for an alternative path to induct medical students into clinical practice.

Feeling Her Way into Clinical Education

When Deepali Bang first started the Longitudinal Integrated Clerkship (LIC) in the second year of her MD studies at Duke-NUS Medical School, she couldn’t help but feel lost. If switching between inpatient immersion and outpatient clinics every few weeks wasn’t enough, the outpatient clinics themselves were a whole new ball game.

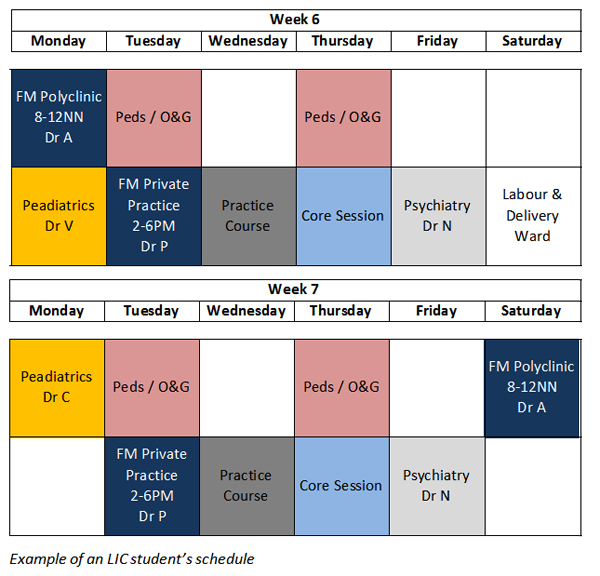

At these clinics, which spread across the island, Deepali was simultaneously exposed to different disciplines, including family medicine, paediatrics, obstetrics and gynaecology, and psychiatry. “Lunch break served three crucial purposes: traveling between the clinics, switching the mind to another discipline and having lunch”; recalls Deepali.

Deepali strived to pick up as much as she could during the various outpatient attachments, but she seriously doubted that she’d ever learn enough this way. It was hard to keep up with the schedule and Deepali wondered if LIC was the right path for her.

“I realised that in the midst of our laser-edge focus and preoccupation with medical issues, we often lose our focus on the patient. We need to constantly reflect and remind ourselves that we are here to help a person.”

- Deepali Bang, Duke-NUS student

Things Began Falling in Place

Just when such doubts seemed to engulf her completely, on came the third round of LIC attachments and the pieces started to fall into place, almost miraculously. Recalling her experience, Deepali said, “At first my clinical knowledge was lacking; as it was tough to read up and learn five disciplines concurrently. Over time, I began to grasp the medical knowledge better, and things started to make sense. Juggling between five different disciplines concurrently started to become fun and challenging.

"We were doing something different every day and maybe this ‘constant-change’ prevented a sense of burnout some of our colleagues were feeling.” added Deepali. She also realized that to succeed in LIC (or medicine) she had to be in-charge of her own learning. Soon, the inpatient to outpatient transitions became seamless and almost natural, like they were meant to be this way.

“Many of the family doctors at polyclinics and private practice have a long-term relationship with their patients. Even if the patients come for common cough or cold, doctors seem to spend a lot of time chatting with patients, checking back on previous ailments and for causal links with their present symptoms. It’s very different from inpatient care, where there is no time for a longitudinal relationship and the focus is usually on the active medical problems” she shared.

What is the Blended Longitudinal Integrated Clerkship? As a clinical education model, Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships (LIC) provide students with integrated exposure to cross-disciplinary experiences concurrently, rather than block to block rotations. This fosters continuity of relationships among students, faculty and patients over time.

Duke-NUS Medical School’s blended model is a hybrid of the traditional block clinical clerkship and LIC models. Started in 2014/2015 with an inaugural batch of six students, the year-long programme alternates inpatient immersion at the hospital with outpatient exposure at outpatient clinics and has in-built self-study periods to instill ownership of learning. .jpg)

|

Soon, Deepali, found herself recognising some of the returning patients at the clinics. “At the psychiatry clinic, when I asked Ms A if she was still suffering from the side effects of her medications, Ms A was pleasantly surprised that I could recall her previous consultation and symptoms”. Such instances, deepening her medical insights and giving a broader perspective gave her immense confidence in handling clinic sessions. The longitudinal nature of the program also helped build a bond of trust and confidence between the clinical mentors and students.

Deepali also appreciated the critical reflection element of the LIC. Over the span of one year, each student had to write a series of reflective essays on challenging or confusing clinical encounters, and share with the LIC faculty and peers for feedback. Many took the opportunity to revisit events, ponder over their personal priorities and ethics, or uncover assumptions about patient-centred care. “The best part about sharing our reflective write ups was that it brought us closer. We were now bonded professionally, personally and emotionally.”

“With hindsight, I realised there were a multitude of emotions cruising beneath each atypical clinical encounter, and that our actions naturally tended to be reactive,” she recounted. “More importantly, I realised that in the midst of our laser-edge focus and preoccupation with medical issues, we often lose our focus on the patient. We need to constantly reflect and remind ourselves that we are here to help a person.”

A Different Route to Patient-centred Care

Deepali’s experience in LIC is in line with one of the main principles of the programme, for students to take ownership of their learning with longitudinal guidance from faculty.

“We are fortunate that colleagues including our administrative coordinator Ranjini, LIC core faculty and students themselves have shown collective ownership of the programme since its inception, and practiced its philosophy of focusing not on what teachers should teach, but on ways to facilitate students’ learning”, said Dr Shiva Sarraf-Yazdi, Assistant Dean for Educational Strategies & Programme Development at Duke-NUS Medical School.

“By building close-knit learning communities in which students have a voice as active participants rather than passive observers … I believe we can more effectively and efficiently enable our young colleagues to make a difference in the care of patients.”

- Dr Shiva Sarraf-Yazdi, Assistant Dean for Educational Strategies & Programme Development , Duke-NUS

Ties are strong within the LIC community and relationships extend beyond the LIC year. Many LIC “graduates” keep coming back of their own accord to help out with peer learning, while core faculty keeps tabs on students’ personal and professional development over time.

“Principles of continuity, be it of patient care or longitudinal relationships with faculty and peers are considered tenets of good medical education practice. We have learned a great deal from our LIC experiences and hope to deliberatively apply some key lessons to the wider student body. These may include longitudinal faculty guidance and peer support, emphasis on outpatient care, integration of disciplines, and cultivation of patient-centric reflective practices that further support our students’ professional identity formation”, Dr Shiva added.

“By building close-knit learning communities in which students have a voice as active participants rather than passive observers, guided by role models who hold them to high standards and foster habits of inquiry, I believe we can more effectively and efficiently enable our young colleagues to make a difference in the care of patients. This is ultimately why we are all here.”

Duke-NUS Medical School will be hosting the 2017 Consortium of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships Conference from 23 to 25 October, a first in Asia. Join in the gathering of academics, faculty, students and staff for a powwow on the future of clinical education.