knee after partial knee replacement surgery

Knee osteoarthritis may be most common in older people but it can affect the young and physically active, especially if there had been previous knee injuries.

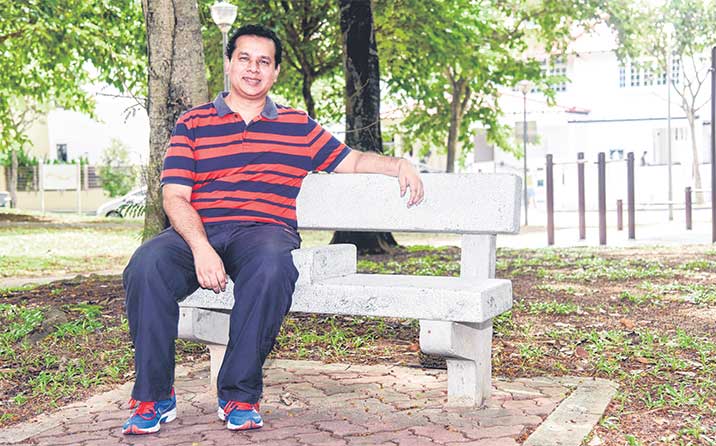

One such person is Philip Muthiah, who tore the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in his right knee playing football 25 years ago.

He had the ligament surgically reconstructed before returning to regular sports activity.

However, early this year, he experienced a sharp pain and instability in the same knee after a minor fall. X-rays revealed severe osteoarthritis in the knee.

“The bones at my knee joint were in contact with each other,” said the 49-year-old physical education teacher.

“My mobility was badly affected and I was getting backaches from shifting my weight to my left side when I walked.”

Osteoarthritis occurs when the cartilage, which cushions the bone ends in joints, deteriorates to the point that the bones begin to rub on each other.

The diagnosis for Mr Muthiah was early osteoarthritis. The condition predominantly affects those aged 60 and above.

Studies have shown that athletes who have suffered ACL injuries are at higher risk of developing early osteoarthritis in subsequent years.

Most of the patients in Singapore who go for ACL reconstruction surgery are in their 20s and 30s.

Overseas studies show that between 25 and 80 per cent of ACL injured knees develop signs of osteoarthritis a decade or more after the initial injury – when patients would be in their 40s.

It is a trend noticed in Singapore in the past few years by some doctors. While the number of people with knee osteoarthritis is expected to continue to rise, owing to an ageing population, more younger patients are showing up.

In recent years, Dr Jeffrey Chew, a consultant orthopaedic surgeon at Mount Elizabeth Medical Centre, has seen an increase of 15 to 20 per cent of younger patients.

He said: “This is probably related to Singaporeans being more physically active in general and more aware that something can be done.” More of them also have previous ACL injuries.

The Straits Times reported in 2012 that some private doctors were seeing a threefold to fourfold increase in patients younger than 50 with osteoarthritis. But it was not known how many of them had sustained ACL injuries earlier.

“It can be difficult to quantify the exact figure for ACL injury resulting in osteoarthritis in the knees, as patients may present to us at varying stages of osteoarthritis,” said Adjunct Associate Professor Lee Keng Thiam, head of Tan Tock Seng Hospital’s orthopaedic surgery department.

ACL injuries are most commonly due to non-contact twisting injuries of the knee, such as in basketball, where a player can twist his knee upon landing after a jump.

If the ACL is damaged, the shin bone can twist and move forward excessively during load-bearing activities, creating abnormally high pressure on the knee cartilage.

With wear and tear over time, it maydevelop into osteoarthritis.

“Injuries to the meniscus, cartilage and underlying bone would further aggravate the risk of osteoarthritis,” said Associate Professor Denny Lie, senior consultant at the Singapore General Hospital's Department of Orthopaedic Surgery.

Younger patients present a challenge for doctors to choose the most suitable treatment.

“Many of these relatively young patients opt for non-surgical treatment, with surgery as a last resort,” said Associate Professor Wilson Wang, head and senior consultant at National University Hospital’s (NUH) orthopaedic surgery department.

He said this might be one reason the percentage of patients under the age of 50 undergoing knee replacement surgery at NUH has remained at 2 to 5 per cent of the total in recent years.

Non-surgical treatment ranges from muscle-strengthening exercises to reconstructing cartilage with stem cells.

If surgery is required, partial knee replacement could be the option as these patients are likely to be mid-career professionals who prefer shorter rehabilitation periods, said Dr Chew.

Up to 30 per cent of patients are not very happy with total knee replacement as it does not feel natural, he added. However, makoplasty, which uses a robotic-guided system, can offer highly accurate partial knee replacements with fast recovery time and the return of function. Patients can be walking again as soon as two to three days after surgery, compared to more than a month for those who have undergone full knee replacement.

Not all of the bone in the patient’s knee is removed in partial knee replacement surgery. As some organic tissue remains, some patients prefer partial knee replacement as the knee feels more “natural” and flexible post-surgery.

However, partial knee replacement is viable only if the arthritis in the knee is limited to the inner or medial compartment.

There are three compartments in the knee joint – the medial, lateral and patellofemoral.

“Athletes who develop tri-compartment arthritis (affecting the whole joint) would need a total knee replacement,” said Prof Lie.

Mr Muthiah’s osteoarthritis had progressed to the point where he needed surgery. As the arthritis was restricted to the inner compartment of his knee and his repaired ACL was in a stable condition, he was able to opt for partial knee replacement. He had it done in August.

“It’s a perfect fit. I feel like I’ve got a brand-new knee,” he said. He was walking a couple of days after surgery and he has been doing physical rehabilitation exercises and going for walks. He also wants to resume cycling soon. “I’m looking forward to the years ahead with a knee that feels natural,” he said.

Contributed by

Get it on Google Play

Get it on Google Play