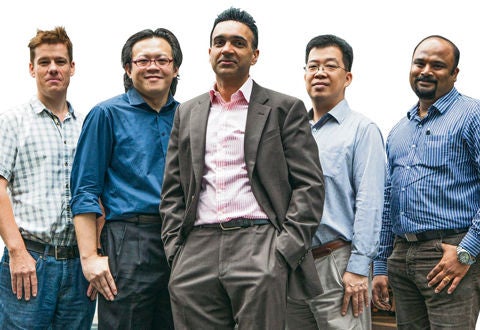

(from left) Dr Matthew Lovatt, Dr Gary Peh, Dr Gary Yam and Dr Elavazhagan M, are delving into tissue engineering and stem cell growth at the front and back of the cornea.

Associate Professor Jodhbir Singh Mehta, a clinical scientist, is heading a team that hopes its research will one day reduce the need for major corneal transplants.

It’s a faraway goal, but research is steaming ahead under his charge.

At the Singapore Eye Research Institute (SERI), Associate Professor Jodhbir Singh Mehta’s team is delving into tissue engineering and stem cell growth at the front and back of the cornea.

Their ultimate goal is to grow corneal cells from donor eyes so that damaged cells can be replaced instead of patients having a total corneal transplant.

An early success was finding a receptor on corneal endothelial cells that deals with oxidative stress, which is a leading factor in Fuchs’ Dystrophy – an eye disease affecting the cornea, in which a transplant may be needed.

This year, Prof Mehta, Head and Senior Consultant (Research), Department of Corneal and External Eye Disease, Singapore National Eye Centre (SNEC), and Associate Professor, Duke-NUS Medical School, received a Clinician Scientist Award from the National Medical Research Council to elucidate this further.

“We managed to find this out, because in a previous study of young and old corneal donors, we found all the oxidative stress defects in tissues from the elderly,” he said. The disease mostly affects people over 50. “People lose about 1 per cent of their endothelial cells each year as they age. The cells pump fluid out of the cornea but when their numbers drop to about 500 to 600, the cornea swells up and people develop cloudy vision.”

Prof Mehta, who does about 100 corneal transplants a year in his clinical practice, said there are not enough donor corneas in Singapore as more people are needing corneal transplants as the population ages.

In the past six years, his team has managed to grow endothelial cells from one donor cornea and expanded them consistently to make tissue engineered constructs, enough to treat about 80 patients. With current transplantation techniques one donor cornea can only treat one patient with Fuchs’ Dystrophy.

“The major hurdle has been to develop a culture system to grow the endothelial cells consistently. These cells are very difficult to expand since they do not divide in vivo, and if they expand too fast they transform into non-functional cells.

“Several units in the US and Germany have been working in this area for 20 years without getting to animal studies. Currently our animal studies are going well and we hope to apply for a clinical trial by the end of the year. Only one other group in Japan has reached this stage.”

Prof Mehta, who hails from the United Kingdom and was trained there, has won more than 25 international awards for his work. He has been in Singapore for the last decade, and he appreciates the support he gets for his research work and the ease of access to top researchers here.

“Here I can finish my meetings in the morning, for example at A*Star or Nanyang Technological University, and travel back to finish my clinical work in the afternoon. In London, it would take me three hours to travel from a meeting back to the office.”

Coming from a family of doctors, Prof Mehta and his brother spent a lot of time around hospitals with their father when they were young. His father was a general surgeon and his brother is a urologist.

“I chose ophthalmology because it has a nice balance of high-level medicine, research and surgery. I chose to be a clinician scientist since every day is different, with different challenges, where we can try to answer the questions posed by the problems we see and face as clinicians.”

Plus, he finds corneal transplants interesting and the results gratifying. “In my clinic, I see blind patients, some able to regain 90 per cent of their vision after transplants. It’s a life-changing event for them and a motivating factor for me.”

Contributed by

Get it on Google Play

Get it on Google Play