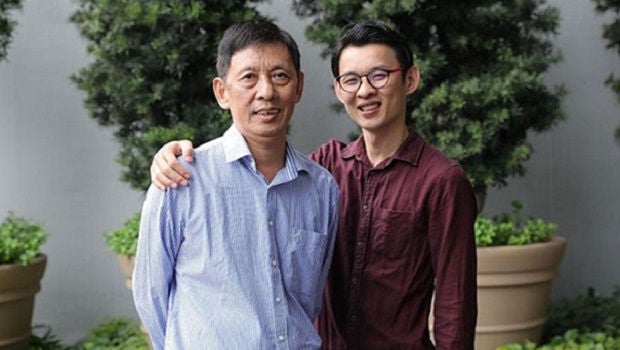

Mr Chen Yu Hui and his son Qingzhong are both recovering well, more than a year after the operation, and continue to go for follow-up medical checks. The elder Mr Chen has B positive blood while his son is A positive.ST PHOTO: ONG WEE JIN

SGH team performs transplant involving living donor with incompatible blood group

Felicia Choo, The Straits Times

Patients needing a liver transplant can now have a higher chance of receiving a donor organ, following the success of South-east Asia's first liver transplant involving a living donor with an incompatible blood group.

Doctors at Singapore General Hospital (SGH) believe that with the patient recovering well from last year's surgery, it will pave the way for similar surgery to be carried out both in the region and Singapore.

In Singapore, there is a growing number of patients on the waiting list for a liver, from nine in 2007 to 52 as of end June this year, based on statistics from the National Organ Transplant Unit.

Associate Professor Jeyaraj Prema Raj, director of the liver transplant programme at SGH, said that such a transplant is an important option to have, especially for patients in dire need - as was the case of Mr Chen Yu Hui, 56.

Without a transplant, doctors predicted that Mr Chen, who was suffering from liver cancer, hepatitis B and liver cirrhosis, had fewer than two years to live. Mr Chen did not qualify for a liver from a dead donor as such livers are prioritised for liver cancer patients with the least likely chance of recurrence. In Mr Chen's case, there was concern that his cancer could recur.

Blood-group-incompatible organ transplants are usually a last resort, said Prof Prema Raj. But it was left to Mr Chen's 32-year-old son Qingzhong to come to his aid. A part of the son's liver was transferred to the father in a 12-hour operation at SGH in July last year.

The elder Mr Chen has B positive blood while his son is A positive.

Preparing the elder Mr Chen for the surgery involved suppressing the production of and removing specific antibodies in his blood - through an intravenous infusion and special dialysis machine - to a level low enough to prevent them from thinking of the donated organ as a foreign body and attacking it.

While kidney transplants involving living donors with blood groups that are incompatible with those of recipients have been performed in Singapore since 2008, this was the first such liver transplant.

As such, the surgical team studied blood-group-incompatible liver transplants in other countries such as South Korea and Japan.

In the first two weeks after the surgery, the elder Mr Chen had to go through another round of dialysis, and the level of antibodies in his blood was measured daily to ensure that it remained low.

For the younger Mr Chen, whose wife was seven months pregnant at the time of the surgery, the desire to save his father overrode any fear.

Both he and his 34-year-old brother volunteered as potential donors, but the younger Mr Chen was deemed more suitable.

"I felt that it was my responsibility as a son and an expression of love to help my father, so I shouldn't be too worried," said the owner of a retail shop, who became a father for the first time when his son was born in November last year.

After surgery, his liver took six weeks to fully grow back and he was back to work after three months.

More than a year later, the duo are both recovering well and continue to go for follow-up medical checks.

According to a 2015 Taiwan study, the five-year survival rates for blood-group-incompatible and compatible living donor liver transplant recipients were similar, at 71 per cent for the first group and 71.5 per cent for the second group.

SOURCE: THE STRAITS TIMES SINGAPORE PRESS HOLDINGS LIMITED. REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION.

Contributed by

Get it on Google Play

Get it on Google Play