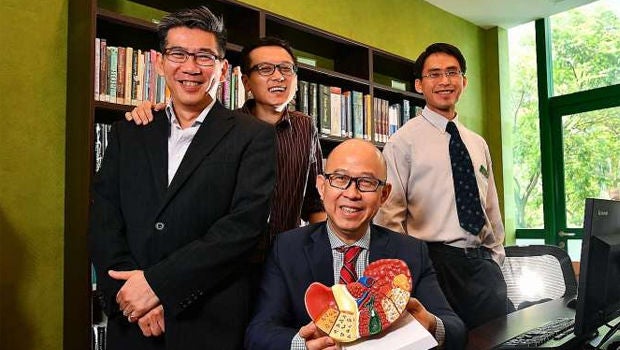

From left: Associate Professor Roger Foo and Dr Zhai Weiwei from the Genome Institute of Singapore, with Professor Pierce Chow (seated), from the National Cancer Centre Singapore, and Dr Wan Wei Keat from Singapore General Hospital. Their work suggests liver cancer treatment should be customised to each patient. ST PHOTO: LIM YAOHUI

By Lin Yangchen, The Straits Times.

A discovery by a team of scientists suggests that treatment for liver cancer should be customised to each patient.

The leader of a team of Singapore researchers doing ground-breaking work into liver cancer turned to the tale of the blind men who touched an elephant to point out that previous studies had wrongly assumed the nature of the cancer from just one point of view, that is, one biopsy.

The team, from the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS) and the Agency for Science, Technology and Research's Genome Institute of Singapore (GIS), found that the genetic characteristics of liver cancer tumours can vary widely, not only across different patients but also across different parts of a single tumour from one patient.

This quashes the prevailing assumption that any given case of liver cancer is caused by a single type of genetic mutation.

GIS' Dr Zhai Weiwei, the study's lead author, said: "It's like touching an elephant only at a single position. The perspective on the elephant is very different depending on which biopsy you take."

Only when the researchers examined multiple slices of surgically removed tumours did they uncover the true character of the "elephant".

Their findings were published last month in the journal Nature Communications. Their work suggests that treatment should be customised to each patient, a concept called precision medicine.

But it also means that drugs used for other cancers might work for liver cancer, since it turns out that some of the mutations in liver cancer are found in other cancers as well. So the team is now looking into these drugs.

NCCS' Professor Pierce Chow, the study's principal investigator, said it sets the scientific basis for clinical trials of new treatments, which he expects to take place within three to five years.

The team made the discoveries by sequencing the DNA, or genetic material, of 66 tumour samples from nine patients at NCCS and Singapore General Hospital.

People had been wondering why the standard drug Sorafenib does not work well on most liver cancer patients, said the researchers.

The kaleidoscopic genetic makeup of liver cancer tumours, which makes a one-size-fits-all treatment ineffective, was not previously realised because the cancer has traditionally been diagnosed with a single biopsy, a procedure which extracts a single liver tissue sample.

Dr Zhai, who used to study the evolution of Neanderthals, a kind of prehistoric human species that went extinct about 40,000 years ago, analysed the genetic relationships of the mutations.

Each patient's tumour was represented by a diagram looking like a tree whose branches denote the different mutations.

A tree that looks like a coconut palm, with many offshoots from a single point, means that the mutations in the tumour are relatively similar to one another.

In contrast, a diagram that looks like a rain tree, with different levels of branching, means the mutations are very different - and the cancer is harder to treat.

Today, if liver cancer is detected in its early stages, the median five-year survival rate is 65 per cent. It is the second-deadliest cancer in the world, after lung cancer.

To take the fight against liver cancer to a new level, the scientists plan to increase their sample size to 100 patients of different ethnicities in four Asia-Pacific countries, with funding from Singapore's National Medical Research Council.

SOURCE: THE STRAITS TIMES. SINGAPORE PRESS HOLDINGS LIMITED. REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION.

Contributed by

Get it on Google Play

Get it on Google Play