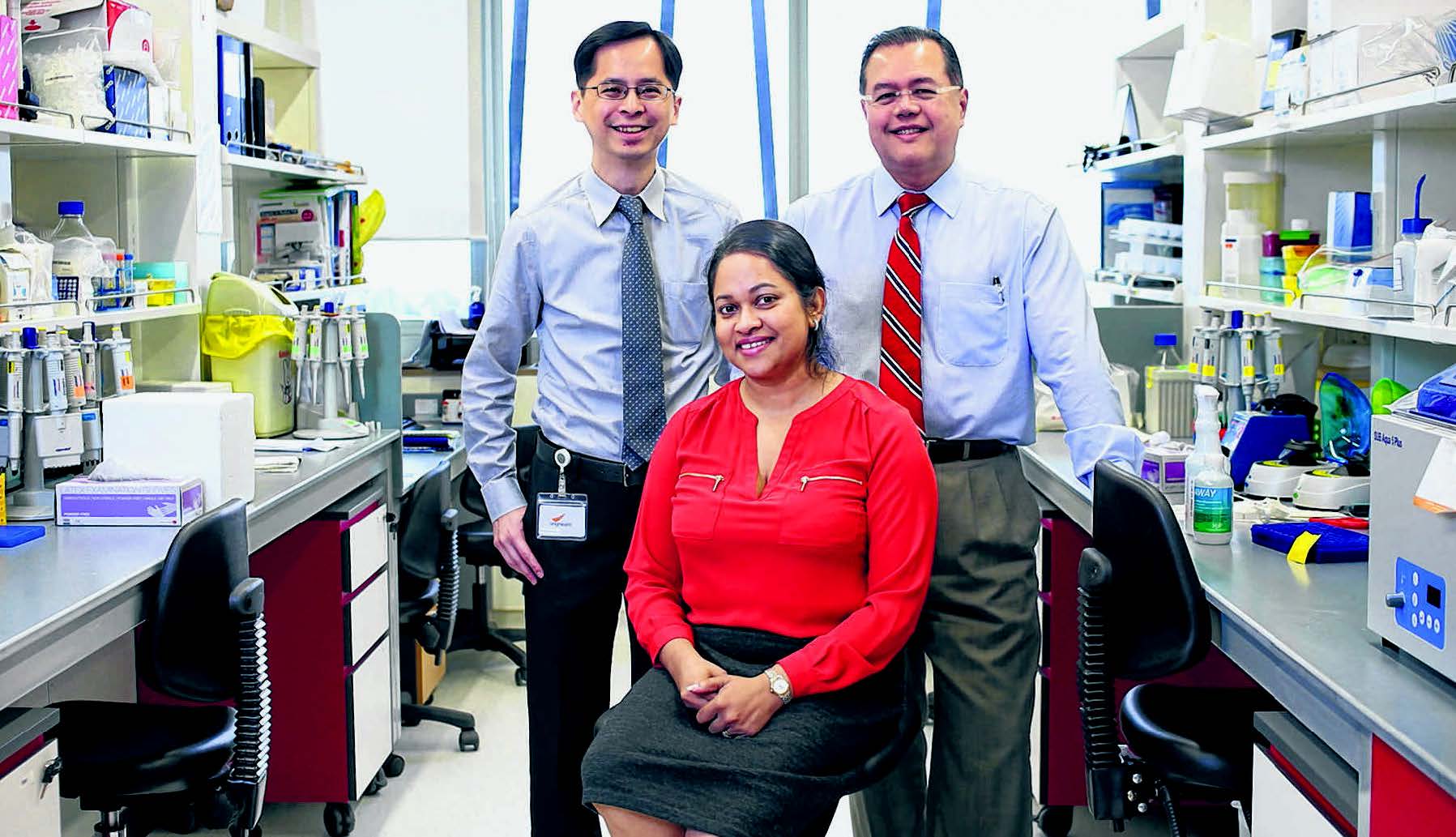

and Professor Aung Tin and their team discovered four genes linked to intraocular pressure and glaucoma risk. Associate Professor Eranga Vithana (seated) was part of a team who found two new genes linked to primary open-angle glaucoma risk among the Chinese. ST PHOTO: ONG WEE JIN

Researchers identify genes that may help them understand eye condition better

Q: Glaucoma is a condition characterised by progressive damage to the optic nerve. In Singapore, it is the leading cause of irreversible blindness, affecting about 3 per cent of those aged over 50. But what causes it?

Associate Professor Eranga Vithana: The hereditary component is a big part of why a patient develops glaucoma, but along with genetic risks, other factors such as age, gender and degree of myopia could play a role too.

The most widely known risk factor linked to optic nerve damage is intraocular pressure (eye pressure). This is due to the reduced drainage of a fluid called aqueous humour out of the eye. The fluid provides nutrients that keep structures in the front of the eye like the lens, iris and cornea healthy.

Currently, intraocular pressure (IOP) is the only risk factor that is treatable. IOP is usually reduced using eyedrops, laser treatment or surgery.

Q: Is it possible to predict a patient’s likelihood of getting glaucoma?

Eranga: It depends on the type of glaucoma. For early onset glaucoma, which affects people before they turn 40, we found that most cases are caused by a gene called Myocilin.

If there have been cases of juvenile onset glaucoma in a family, the rest of the members should undergo screening for this gene even before symptoms such as disappearing side vision appear.

But it is very difficult to predict late onset glaucoma. That is why we are trying to find genes linked to it. When there are enough known genes linked to the disease, we can one day do some sort of risk profiling for patients. But this is a long way ahead.

Q: Last month, two studies done by scientists at the Singapore Eye Research Institute (SERI), the Singapore National Eye Centre, the Genome Institute of Singapore and the National University of Singapore were published together in the prestigious science journal Nature Genetics. What can you tell us about the studies?

Professor Aung Tin: One study discovered two new genes linked to primary open-angle glaucoma risk among the Chinese. This type of glaucoma makes up between 70 and 80 per cent of all glaucoma cases worldwide, and is due to poor aqueous outflow.

The other study done among Asian, European, American and Australian populations identified four genes that could affect intraocular pressure and risk for glaucoma.

This discovery could help us understand glaucoma better. In the future, it could also help in the screening and early diagnosis of the disease, or in the assessment of the risk profile of patients. Now that we have identified these genes, the next step is to find out what they do and their role in the glaucoma pathway, and if there are any potential targets for therapy.

Eranga: Once we find out the catalogue of risk genes associated with the disease, we can study how these genes work and the mechanisms by which they cause disease. Ultimately, we are working towards more specialised, personalised therapy. By knowing the genetic markers important to the disease we hope to develop treatment tailored to patients’ genetic makeup.

Q: What surprised you about the studies?

Aung Tin: The interesting thing is that the same gene, ABCA1, came out in both studies. Researchers used two different approaches, and found the same gene.

Eranga: This means that the ABCA1 gene is responsible for two aspects – it controls IOP and is also able to act as a risk factor for primary open-angle glaucoma. So we speculate that patients with these variations in this gene could be developing glaucoma through increased IOP.

Associate Professor Cheng Ching-Yu: In the study on IOP, blood type was also found to be related to IOP – this is a new factor that emerged only from this study. It appears that people with B blood types are more prone to developing higher IOP. But exactly how blood type contributes to the disease remains unknown.

Q: In September, SERI completed its move into the new Academia building on the Singapore General Hospital campus. Why move?

Aung Tin: The move is a consolidation of our four sites that were previously in places such as the National University of Singapore and Jalan Bukit Merah.

In the past, it was difficult to operate when we had four different sites. Holding meetings and communicating with colleagues was not efficient. We also wanted to be located next to the hospital, to have better access to patients, and so we could communicate with our doctors who interact directly with patients.

In the next few years, we hope to build up three new research programmes in myopia, health services research, and medtech or devices, and in the long term, to develop more translational research and industry collaborations.

Associate Professor Cheng Ching-Yu

Associate Professor Cheng Ching-Yu, 46, is a senior clinician scientist at the Singapore Eye Research Institute (SERI).

Like Professor Aung Tin, he was part of a team of researchers behind a discovery of four genes associated with intraocular (inner eye) pressure and glaucoma risk.

The study was published in a science journal last month. Prof Cheng said he considered the breakthrough one of his greatest achievements in glaucoma research.

“This discovery is not only part of the results of our 10-year effort in eye epidemiological studies, but also the efforts of the glaucoma international consortium which involves 18 sites across four continents,” said Prof Cheng.

He and his wife, who is also an ophthalmologist at SERI, are expecting a baby at the end of this month. “My wife also enjoys both research and clinical work... and she fully understands the nature of my work,” he added.

Although he goes home late on workdays, Prof Cheng said he makes the effort to “keep away from his laptop and e-mail for two to three hours” to have dinner with his wife and catch up on daily happenings.

Associate Professor Eranga Vithana

The eye and how it works has been Associate Professor Eranga Vithana’s focus for the past two decades.

Ever since she embarked on her PhD studies more than 20 years ago, the head of the Molecular Genetics Laboratory at the Singapore Eye Research Institute (SERI) has been doing research on the organ responsible for our vision.

“As sight is one of the most important senses, working to help preserve it is important,” said the 41-year-old. Prof Vithana was part of a team who had last month discovered two new genes linked to primary open-angle glaucoma risk among the Chinese.

In 2005, she was also part of a study that discovered a gene for a congenital form of corneal dystrophy – a rare childhood blindness. “It was quite an interesting time for me as I had my daughter in 2005 as well,” she added.

She also has a son, who is five, and as a mother, the eye specialist ensures they protect their eyes by reducing time spent in front of the computer or television, and by urging them to spend time outdoors.

Professor Aung Tin

For visionary eye doctor Professor Aung Tin, executive director at the Singapore Eye Research Institute (SERI), glaucoma research is his passion.

He is best known for his insights into angle closure glaucoma, which is the type half the people get.

For his work in the field, Professor Aung, 48, was one of three doctors in Singapore who, in May, made it to the list of the world’s 100 most influential people in ophthalmology by a British professional journal.

More recently, the father of three girls was part of a team of scientists from SERI, the Singapore National Eye Centre, the Genome Institute of Singapore and the National University of Singapore who made two discoveries on genetic markers linked to primary open-angle glaucoma and intraocular (inner eye) pressure, which is associated with glaucoma.

Both studies were published in science journal Nature Genetics last month. Prof Aung said: “I do enjoy... treating and helping my patients individually, but research has the power to positively affect more people outside one’s own practice.”

Contributed by

English

The Sunday Times - SNEC and SERI Eye docs see glaucoma more clearly.pdf

Get it on Google Play

Get it on Google Play