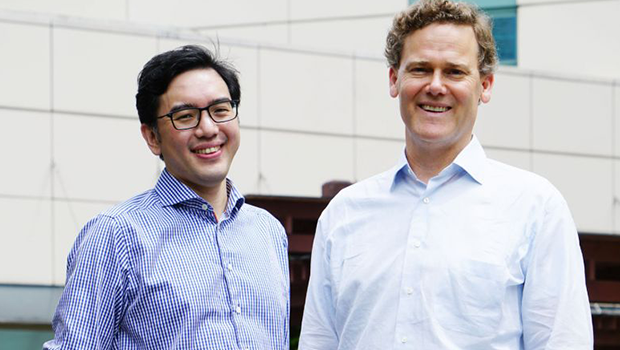

Assistant Professor Nicolas Kon from the National Neuroscience Institute and Associate Professor Michael Lucas James from Duke University School of Medicine are the lead researchers in the trials. PHOTO: NATIONAL NEUROSCIENCE INSTITUTE

Non-surgical treatment for people who have suffered a more severe form of haemorrhagic stroke could be on the cards if trials here and in the United States prove successful.

Researchers are testing a protein-based compound that reduces inflammation in the brain after injury. It would complement existing treatment for the affliction, which makes up about one-fifth of all stroke cases here but caused 44 per cent of all stroke-related deaths in 2016.

"Haemorrhagic stroke is one of the most frequent emergency admissions that we get, but we find that the current standard for treatment is very limited," said Assistant Professor Nicolas Kon, director of Neurosurgery Research at the National Neuroscience Institute.

This type of stroke happens when a weakened blood vessel bursts and bleeds into the surrounding brain.

Patients are treated with blood pressure-lowering drugs to limit the increase in the size of the clot in the brain. More severe cases require surgery to remove the clot, said Prof Kon.

Associate Professor Michael Lucas James from Duke University School of Medicine in the US noted: "The clinical trials that have been run and finished to date don't show improvement in neurological recovery after having surgery for haemorrhagic stroke, although there are ongoing trials looking at newer technology that may or may not have benefits. So you have an opportunity to provide an effective treatment through the compound for a larger group of patients that may or may not respond to surgery."

Researchers at Duke University took 20 years to develop the compound, which is made from a protein produced in the brain.

Researchers at Duke University took 20 years to develop the compound, which is made from a protein produced in the brain.

The compound is given to patients through an intravenous drip every six hours in hospital for three consecutive days to regulate inflammation. They are then monitored for three months to see if the compound improves their function and mortality after one and three months.

"We don't have the full results yet, but it appears to be safe," said Prof James, who is the research lead for the US study. "We haven't had any serious, adverse effects of the drug."

The US trial, which involves 38 patients, started two years ago and ends in June. The local trial started recruiting patients, mainly from Singapore General Hospital and Tan Tock Seng Hospital, this month.

Researchers aim to recruit 60 patients aged 30 to 80 for the trial, which will conclude in 2021. It is randomised, meaning that half of the patients recruited here will get a placebo instead of the compound.

"This particular trial is critically important for a number of reasons," said Prof James.

"One of the reasons is if it works, it would be the first therapeutic drug for haemorrhagic stroke and it would be the first trial that's run congruently in Singapore and the US."

Singapore was chosen for the trial because the incidence of haemorrhagic stroke here is twice that of the US.

Between 18 per cent and 24 per cent of stroke patients in Asia suffer a haemorrhagic stroke, compared with between 8 per cent and 15 per cent of patients in the West.

Both countries also have a similar standard of care and have multi-ethnic populations, added Prof James.

Get it on Google Play

Get it on Google Play