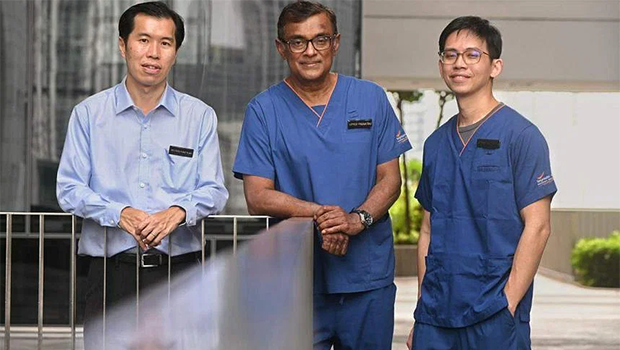

(From left) Dr Chiou Fang Kuan, head of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Service for paediatrics at KKH, Associate Professor Jeyaraj Prema Raj, director of the Liver Transplant Programme at SGH, and Associate Professor Koh Ye Xin. ST PHOTO: DESMOND WEE

Singapore carried out its first intestinal transplant in April 2022 after several years of preparation.

While the first such transplant in the world was done in the late 1960s, the chances of surviving one year were fairly low in the initial years. But this has since improved significantly.

Cambridge University Hospital, which leads the world in successful intestinal transplants, states on its website: “Over the last five years, we have had excellent results and our current three-year survival is over 90 per cent, which is better than reported results from any centre internationally.”

While the need for such transplants is not high, there are currently about 30 children and adults here who may need it when they run out of other options. A registry has been set up and their names are on it.

Intestinal transplant in Singapore is currently a pilot scheme, requiring Ministry of Health approval on a case-by-case basis.

It is being evaluated and a decision will be made later on whether to establish it as a regular programme, like liver, heart, lung, kidney and cornea transplants.

The decision to provide such a service in Singapore followed an informal meeting in 2015 between Associate Professor Jeyaraj Prema Raj, director of the liver transplant programme at the Singapore General Hospital (SGH), and Dr Chiou Fang Kuan, head of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition service for paediatrics at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH).

The two men spearheaded the move to embark on the pilot scheme.

A joint statement from SGH and KKH said: “In the event of an irreversible intestinal failure, when standard therapy such as long-term total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is no longer viable, and when conservative medical treatments are ineffective, or have given rise to significant life-threatening complications, an intestinal transplant is considered.”

TPN involves giving a special formula intravenously to provide the body with nutrients it needs but cannot absorb from the digestive track.

Dr Chiou spent a year at Birmingham Women’s and Children’s Hospital in Britain, which has one of the largest and most experienced paediatric intestinal transplant programmes in the world, having started its programme in the late 1980s.

Separately, about four years ago, Prof Prema Raj, sent a young transplant surgeon, Associate Professor Koh Ye Xin, to study for a year at Cambridge University Hospital.

In Britain, the intestines come from dead donors.

The two transplants in Singapore were done with living donors – both the fathers of the girls.

An international committee of five experts was set up to review the steps before the first transplant in Singapore was done, and Professor Debra Sudan, a world-renowned intestinal transplant surgeon from Duke University Medical Centre came to Singapore for both transplants.

Prof Sudan was the lead surgeon for the recipient, while Prof Koh was the lead surgeon for the donor and also helped with the recipient. They were supported by seven other surgeons, five anaesthetists and two backups, and 10 operating theatre nurses and another six as backups, as well as many other healthcare personnel.

The multidisciplinary Singapore team drawn from SGH and KKH also had 10 practice sessions on animals, as well as a dry run in the two adjoining operating theatres to make sure everything was in place before the actual surgery.

The first transplant was successful, and the girl is doing well.

The second transplant, lasting from 8am to 3.30pm, was done in April this year on another girl of the same age with a similar problem, and she, too, is recovering well.

Both procedures were performed at KKH.

Get it on Google Play

Get it on Google Play