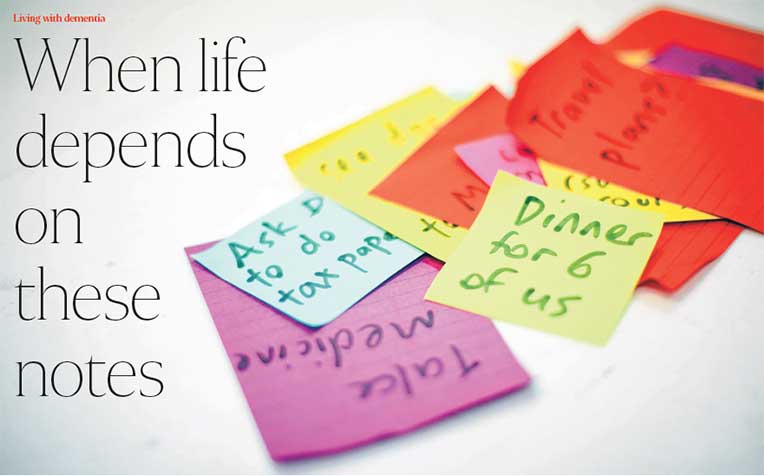

relies heavily on Post-it notes stuck in prominent places to remind her of daily tasks.

Mrs Teo had felt that something was wrong with her for more than a year before she discovered the cause. She was diagnosed as having mild dementia at the age of 66 in 2013.

She has an interest in current affairs and reads magazines such as The Economist and Forbes. But she found she could no longer follow newspaper reports – by the third paragraph, she had forgotten what the first paragraph was about.

She had always been a “scatterbrain”, she confesses, the kind who persistently misplaces her spectacles. But this was more than being absent-minded.

Mrs Teo, who does not wish to use her real name, sometimes loses the thread of conversations within minutes. Neither could she do simple mental sums. She had to add or subtract the numbers on paper “like a Primary 1 kid”.

Although dementia patients are often unable or unwilling to call attention to their condition, her reaction to her diagnosis was unusual– she felt relief.

The 69-year-old housewife says: “I was relieved that at least there is a word I could connect to what I have.”

Her husband of 43 years took it harder. “I was devastated. I thought she was just forgetful. I didn’t think it would be that bad,” says Mr Teo, also 69. “Until now, I haven’t told her what I thought about her diagnosis because I wasn’t sure how she would take it herself. But she was very positive.”

The couple have two sons in their early 40s, as well as four grandchildren. Mrs Teo says: “I don’t think my sons realise the difficulties I have. I still organise meals and badminton games at our home for their families.”

Three years on, however, she remains positive and even hopeful. Faced with an uncharted length of time between her early-stage diagnosis and the ravages of dementia that may eventually come her way, she has a can-do attitude.

“The important thing is acceptance. We’re practical people. Dementia is a new world. You have to learn what to do,” she says.

“I expect the illness to progress. What matters is how long I can maintain my status quo.”

Dementia has a brutal public face. Besides stealing one’s memories, the illness, which affects the brain, can alter a person’s identity. In some advanced cases, sufferers can no longer speak or recognise their loved ones. Some also cannot shower or eat without assistance.

After her diagnosis, Mrs Teo took part in a month-long programme at the National Neuroscience Institute that taught her how to manage her illness.

To cope with forgetfulness, she makes lists and uses transparent containers instead of opaque ones because she cannot remember what is in each storage container once she closes it.

“I survive by using a lot of Post-it notes,” she adds.

She sticks these notes in places where she cannot miss them – on her desk, the dining table or clipped to her handbag.

They remind her of her daily tasks, such as sending a get-well card to a friend; giving her grandson the new clothes she bought for him; or listing the groceries she needs when she goes to the market.

Meticulous by nature, she would stick notes for her domestic helper on the fridge, for instance, instructing her to cook at least 50g of spaghetti for each family member for dinner. The couple live by themselves with their helper.

Besides keeping a healthy diet and ensuring she has enough exercise and sleep, she also takes medication called Aricept – these measures help her manage the illness and could slow its progress.

She regularly attends a programme at the Alzheimer’s Disease Association, together with her husband. This comprises activities dealing with cognitive function and fine motor skills, such as doing craftwork, puzzles and games.

Mrs Teo’s late mother had a form of the illness called vasculardementia, but family history is only one of a few possible risk factors for dementia, which the elderly are more susceptible to.

When she noticed her symptoms, she talked to her doctor, a general practitioner, about them, but he dismissed her concerns.

Three years ago, she accompanied her husband, a retired company director, to the hospital for a routine check-up following his recovery from prostate cancer a few years earlier. There, she chanced upon a hospital newsletter advertising a screening test for dementia and signed up for it at the National Neuroscience Institute.

There are days now when she experiences frustration and short temperedness. “It’s like a double whammy. My memory is not so good and I have lost my independence,” she says. “I can’t learn new things. I have to depend on my husband.”

About two years ago, they bought a new family car, which had “more electronics”, she says. She could not master the more complicated way of starting the new car.

This was compounded by an increasingly problematic sense of direction, another symptom of dementia. So she has given up driving, along with relinquishing to her husband the duties of paying bills and filing bank statements.

Neither does she trust herself to sign cheques. Simple words sometimes elude her and she fears she will write the wrong name or amount on a cheque.

She feels less efficient and, therefore, less confident. “I don’t know whether it has to do with dementia or old age,” she says. “I’ve always handled everything in the house, but now, I feel wishy-washy about decisions such as changing the upholstery.”

Still, she retains much of her capabilities, so much so that dementia can take a back seat. Because she is in the early stages of the illness, her condition, while not a secret to family and good friends, is not fully acknowledged.

Her younger sister, who is in her 60s, has told her: “You don’t have dementia lah.” Mrs Teo says: “I still do a lot of things I like.” She enjoys going to classical music concerts and has travelled to exotic locales such as The Galapagos Islands since her diagnosis.

Among the more than 20 files of newspaper articles and other information she keeps on all kinds of topics – “Knowledge is important to me,” she says – is a file compiling articles about dementia.

She feels “hope, knowing that the scientific community is working on dementia”. “Someone, somewhere is doing something about it, though a cure will probably not be discovered in my lifetime.”

Yet she “never thinks” about what having dementia holds for her in the future– she is too busy to dwell on this unknown. “My only worry is if my husband passes on. I don’t think there’s anyone who can look after me as well as he does.”

Contributed by

Get it on Google Play

Get it on Google Play