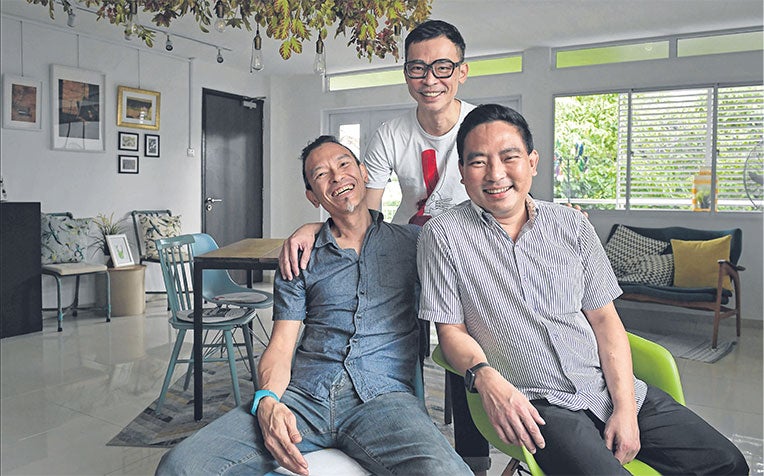

In January last year, Leslie donated his left kidney to Leroy, who was diagnosed with end-stage kidney failure in 2013. Both older brothers had quickly stepped forward to be donors, but one obstacle followed another before the successful transplant was carried out at the Singapore General Hospital. ST PHOTO: KUA CHEE SIONG

Brothers Leslie and Lionel Tan have been known for beguiling audiences across the world as part of renowned local string chamber group T’ang Quartet for more than 20 years.

However, behind the curtain was a difficult period of about four years that the brothers experienced privately as a family.

Their younger brother, Leroy, 47, was diagnosed with end-stage kidney failure in 2013, a result of complications that arose from diabetes.

Although 52-year-old Lionel and Leslie, 54, had quickly stepped forward as donors, it took four years for Leroy to be relieved of the need to undergo regular dialysis sessions.

Leroy, a lawyer, received Leslie’s kidney early last year following a successful operation at the Singapore General Hospital (SGH).

The effects of the surgery could be seen immediately, said Lionel.

“His skin cleared so much – it was starting to get very dark because of the build-up of toxins in his blood. It was a huge difference.”

As the brothers speak of the arduous journey leading up to the operation, the chemistry between them is evident in their easy banter, revealing little of hardships past.

Said Leroy: “It was just one obstacle after another, so it was a relief that the operation went through.”

The first roadblock came in 2013. After months of tests to affirm the brothers’ eligibility as donors, doctors discovered a cyst in Leslie’s liver that required him to have surgery, snuffing out any hopes of him being a donor.

Lionel managed to clear all screenings and was deemed a suitable donor for his younger brother.

But a day before the operation was scheduled to take place in 2013, the brothers were hit with yet another unexpected piece of news.

“I was at home packing my bags when I got a call that we had to call off the operation because Leroy had fallen ill,” said Lionel.

The brothers had no choice but to postpone the transplant for a year till the illness was cleared from Leroy’s system.

Leroy, who is married with two teenage children, was back to fivehour dialysis sessions, thrice weekly – posing a major strain on both his work and family.

By then it was 2015, and SGH had temporarily suspended its kidney transplant programme due to an outbreak of hepatitis C infections. Leroy’s hopes for a healthy reboot were dashed again.

In the meantime, Leslie was deemed a suitable kidney donor after post-surgery screenings. Doctors also said they preferred him as the organ donor. The transplant was then slated to take place in January last year.

In one final hurdle, on the day of the operation, both Leroy’s and Leslie’s blood pressure were found to be too high, delaying the procedure yet again.

“It was very frustrating,” said Leslie. “I went home and locked myself up in my apartment. I didn’t want to go out because I didn’t want to go out and get the flu and then delay the transplant some more.”

Finally, a week later, the agonising wait was over: Leroy successfully received Leslie’s kidney in late January. Lionel said it was an emotional day for the family.

“I was happy to see that everything worked out... My mum was extremely stressed and worried, but afterwards she was ecstatic.”

Leroy was diagnosed with diabetic nephropathy in 1998.

Dr Kwek Jia Liang, a consultant at SGH’s department of renal medicine, explained that diabetic nephropathy is damage to the kidneys arising from diabetes mellitus.

It leads to a loss of kidney function. “It can result in end-stage kidney disease with complications such as fluid overload, electrolytes imbalances and build-up of metabolic toxins, which can affect the functions of multiple organs such as the heart and brain,” said Dr Kwek.

Leroy began noticing swelling in his legs in 2013 and was diagnosed with end-stage kidney failure.

The disease took a serious toll on his daily life. He was constantly tired and even threw up occasionally after dialysis sessions. The lawyer, who runs his own firm, had little choice but to scale down on activities such as volunteering for grassroots activities and travelling.

Meanwhile, Lionel and Leslie began reading up on Leroy’s condition and offered him brotherly support. “When you see people going through dialysis, you don’t think much about it. But then you actually see it happening in the house... then you realise kidney failure is truly a horrible thing to have,” said Leslie. So when the time came for them to step forward as donors, it was something the brothers did without hesitation. In fact, they jumped at the opportunity.

“I found out later that people felt that it was such a big deal, but come on...You don’t think about these things, right?” mused Leslie.

“You don’t think about whether it’s successful or not. You just go ahead and do it because it’s saving someone’s life,” said Lionel.

“It’s a big deal but not to the donor. I think it’s a much bigger deal for the recipient,” Leslie added.

Figures from the Ministry of Health show that a total of 40 living donor transplants were performed last year, up from 35 transplants in 2013. However, the number of patients on the waiting list for kidney donation, though falling, still remains significant at 247 last year.

Dr Kwek said although both dialysis and transplants prolong and sustain patients’ lives, transplants result in far more ideal outcomes.

“In Singapore, five-year survival in living kidney transplantation is 96.6 per cent compared to 34.6 per cent to 59.5 per cent in dialysis populations. Kidney transplantation also improves patient quality of life,” he added.

The brothers also stressed the importance of being educated about organ donation. “There shouldn’t be a stigma attached to it. I’m back to my normal self, I’m quite active, and I’m living more healthily,” said Leslie.

Leslie said the other members of the quartet, violinists Ng Yu-Ying and Ang Chek Meng, were supportive during this period by accommodating the brothers’ demanding schedules.

“Everyone went through the whole process with us,” he said.

Kidney transplant is best treatment option

A kidney transplant is, in simple terms, the process of surgically removing a kidney from one person and implanting the organ into another person.

It is the best means of treating end-stage kidney or renal disease, as the transplanted kidney can substitute almost fully the lost functions of the failed kidney.

While dialysis is a life-saving treatment, it does only 10 per cent of the work that a functioning kidney does, according to the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Centre in the United States. It can also cause other health problems.

Transplanted kidneys can come from living or dead donors.

The patient may receive a kidney from a family member, a spouse or a even a stranger, though the most compatible match is usually a sibling, as their genetic make-up may closely match, according to the National Kidney Foundation here.

The patient can also receive a kidney from a person who has recently died. This is known as a cadaver renal transplant.

The average waiting time for a kidney transplant here is nine years. There are patients who are not suitable or eligible for transplants because of their medical conditions and age. Hence, they will need to remain on dialysis.

Although life will be easier for those who can get a kidney transplant than those who are on dialysis, the organ recipients will need to take medicines every day to make sure their immune system does not reject the new kidney.

Unfortunately, a kidney transplant does not last forever.

The average lifespan of a transplanted kidney is 12 years for one from a dead donor, and about 15 years for a transplant from a living donor who is related, according to Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Centre.It affects every two out of three patients reaching endstage kidney disease.

The Straits Times, Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reproduced with permission.

Contributed by

Get it on Google Play

Get it on Google Play