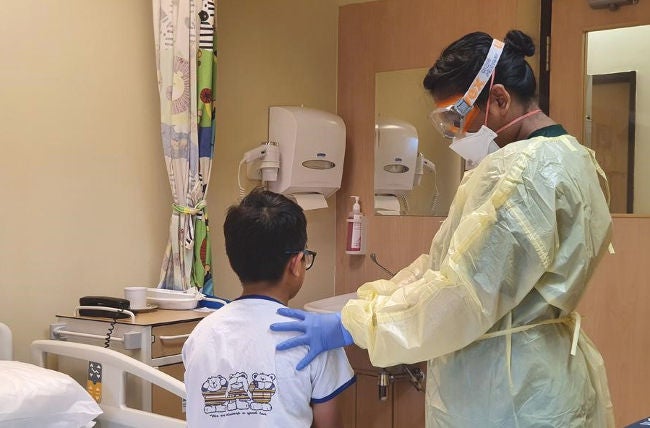

As the leading tertiary referral centre for women’s and children’s health in Singapore, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH) serves as the principal hospital for paediatric COVID-19 cases in Singapore.

This review of KKH’s paediatric infectious disease perspective and experience caring for children with COVID-19 from January to May 2020 may have useful implications for paediatric and community health professionals.

Adult-to-child transmission

In Singapore, COVID-19 screening was implemented for all paediatric household contacts of persons with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

Between March and April 2020, among 137 households with a total of 223 adults with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2, 213 children under the age of 16 years were tested for COVID-19 and 13 children were confirmed to have COVID-19.2 This describes a transmission rate of 6.1 per cent among children and 5.2 per cent of households for the time period.2

The risk of secondary infection in children was highest if the index COVID-19 patient was the child’s mother (11.1%), compared to the father (6.7%) or a grandparent (6.3%). Adult-to-child transmission rates were similar regardless of the gender of the child.2

The youngest age group (0-4 years) had the lowest rates of infection (1.3%) compared to older age groups (8.1% for 5-9 years, 9.8% for 10-16 years) following exposure to a household member with COVID-19. Some studies have suggested that younger children are more resistant to SARS-CoV-2 at a cellular level but there is an urgent need for more research to understand this phenomenon.2

The very low adult-to-child household transmission rate amongst children under five years old also suggests that strict compliance with infection control may be able to mitigate or reduce the risk of transmission from adults to children in household settings.2

Transmission risk of SARS-CoV-2 in educational settings

Screening of children by KKH from three potential SARS-CoV-2 incidents in three educational settings (a secondary school, and two preschools) did not detect evidence of paediatric SARS-CoV-2 transmission. The data suggest that young children may not be primary drivers of SARS-CoV-2 transmission especially in pre-schools.6

These findings suggest that the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission among children, especially young children in pre-school settings is likely to be low. More school transmission studies are urgently needed to inform the development of evidence based strategies to control COVID-19 in our educational settings.

Symptomatic vs asymptomatic children

From January to May 2020, 61.5 per cent of the children with COVID-19 were symptomatic, mainly presenting with low-grade fever (54.2%), rhinorrhoea (45.8%), sore throat (25%), diarrhoea (12.5%) and loss of smell or taste (5.4%).1

A significant proportion (38.5%) of children with COVID-19 were asymptomatic.1 This finding underscores the importance of early screening and isolation of children exposed to an index case of COVID-19.

The highest proportion of symptomatic cases was found in the youngest age group (75%, 0-4 years) compared to older age groups (52.9% for 5–9 years, 64.3% for 10–16 years). Symptomatic children did not have a poorer clinical outcome compared to asymptomatic children.1

All the children had a mild disease course and were discharged well, with a mean length of hospital stay of 15 days.

Viral load dynamics

Examining data from children with COVID-19, higher viral loads were discovered in the nasopharynx of symptomatic children, indicating the possibility of higher transmissibility.3

Both groups of children experienced peak viral loads occurring around day 2-3 of illness/diagnosis, suggesting viral shedding and transmission in the pre-symptomatic phase.3

Within this group, the mean duration of viral shedding was about 16 days, and the longest duration of viral shedding was 30 days in a previously symptomatic child.3

Understanding the temporal trend of COVID-19 viral load in Singapore children is critically important to estimate their transmission potential and postulate the role of children in the transmission of COVID-19 in the community.3

Nasopharyngeal vs saliva and buccal screening

A review of daily nasopharyngeal and bilateral buccal swabs taken for 11 children with COVID-19, found that the buccal specimens contained substantially lower viral loads compared with nasopharyngeal specimens. Two children had negative buccal specimens despite detectable nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2.4

The sensitivity of buccal swabs compared with nasopharyngeal swabs ranged from 25% to 71.4% on different days of collection during the first week of illness/diagnosis. Buccal COVID-19 was undetectable by day 8 of illness/diagnosis, despite continued detection of the virus in the nasopharynx.4

Separately, laboratory RT-PCR testing of nasopharyngeal and saliva specimens from 18 children with COVID-19 revealed a peak saliva sensitivity of 52.9 per cent and cycle threshold trend suggesting lower viral load compared to nasopharyngeal swabs. In five patients, saliva specimens persistently tested negative for SARS-CoV-2. In another five patients, saliva that initially tested negative on days one to three, turned positive on days four to seven.5

While saliva specimens have shown promise for diagnosing COVID-19 in adults, with some studies showing a peak sensitivity of 96 per cent, the utility of saliva specimens in children is low.5

Saliva and buccal specimen collection alone do not appear to be a good screening modalities for COVID-19. Nasopharyngeal swabs remain the recommended upper respiratory tract specimens for screening and detection of COVID-19.4,5

Conclusion

Understanding how COVID-19 affects children differently from adults is very important to guide clinical management of children with COVID-19 and recommendations for community health measures. There is an urgent need for more studies on the paediatric population in order to guide the development of evidence-based effective strategies for clinical management and public health control.

| The study authors would like to thank all the staff of the Microbiology Section, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine; Infection Control and Epidemiology, and Contact Tracing teams; Department of Paediatrics and Division of Nursing, KKH for their dedication and commitment in the challenging working conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

References:

|

Get it on Google Play

Get it on Google Play