The new Acute Medical Ward at SGH takes a different approach to care model to meet the growing demands of an ageing population.

Care for some A&E patients at Singapore General Hospital (SGH) is being intensified and fast-tracked to allow discharge of this select group to be more timely. It is a work model that is being hothoused in the Acute Medical Ward (AMW), which will have more beds when it moves into a new hospital block to be built to also house a much bigger A&E.

This care model involves a couple of key elements: a multi-disciplinary team where nurses play an elevated role, and the use of so-called clinical care pathways, which map out the steps and treatments to be taken for specific diagnoses as a way of standardising the care of these conditions.

“The AMW is a short-stay ward that will treat patients sent from the A&E. They are not critically ill, yet not well enough to be sent home, so are unlikely to need a prolonged hospital stay. Their condition makes a discharge within 72 hours – one of the criteria for admission to the AMW – possible,” said Dr Tharmmambal Balakrishnan, Consultant, Department of Internal Medicine, SGH.

"The main goal of the AMW, is to acutely diagnose patients' problems, stabilise the [condition of the] unwell, and front-load their treatment management so that their overall stay is shorter”.

Dr Lim Wan Tin, Associate Consultant, Department of Internal Medicine, SGH.

For now, not everyone who turns up at the A&E will be admitted to the AMW Patients suffering from pneumonia and other infection-related problems, making up about 45 per cent of the 19,000 A&E patients seen by internists in 2012-2013, were singled out for admission during the pilot in 2015-2016.

Patients who were seen for other problems too diverse to be grouped were treated as before – stabilised and then either discharged or referred to other disease-specific wards in SGH. A largemajority of SGH A&E patients are elderly, with multiple medical conditions.

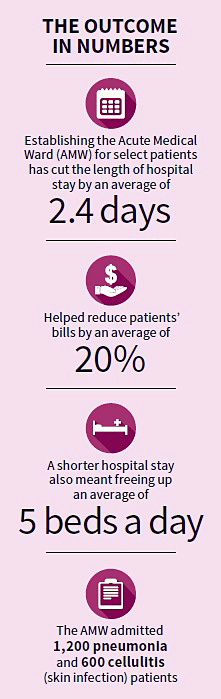

The AMW care model was found to be promising in terms of reducing the length of hospital stay and freeing up more beds at the regular wards. Patients benefited from paying a smaller bill for staying fewer days in hospital.

Introducing this new model of care was not easy because it involved changing work flow and processes. Communications within the team is crucial. Besides the usual morning doctor rounds, all four teams running the AMW – including doctors, nurses, pharmacists, physical and occupational therapists, medical social workers and dietitians – meet mid-morning to discuss cases.

This discussion, unusually, is led by nurses. Most familiar with the patients' conditions, the nurses constantly monitor patients’ vital signs, note improvements or deterioration, and provide valuable feedback about patients’ readiness for discharge. “This discussion helps reduce over-reporting to doctors, and empower nurses, pharmacists, therapists and medical social workers to act with greater autonomy,” said Dr Lim.

The nurses are encouraged to exercise their initiative and recommend appropriate action for the patients. “If a patient who has pneumonia experiences a functional decline, meaning he was able to walk before but is now not able to, the nurse might suggest having physio input,” said Ms Hartini Osman, Nurse Clinician, SGH.

“Previously, we didn’t have the opportunity to have this [morning] discussion in one location, so we had to wait for the allied health professional – say, physiotherapist or social worker – to come in before we could make our recommendations. With this meeting, we can do so immediately.”

Front-loading or intensifying treatments from the start of admission is crucial in boosting recovery, said Dr Tharmmambal, adding that studies show patients’ conditions can deteriorate if not treated quick enough.

Another unusual feature of the care model is that it’s ward-based. The key healthcare professionals are based in the AMW. Before, the internists – who specialise in a broad spectrum of diseases – had to “run around” to see patients, who were admitted to different wards located in different buildings. A patient who needed urgent care for a leg infection, someone with pneumonia and another with chest pain might be put in different wards, but they would be seen by internists first before being referred to their respective specialists, if necessary.

Having patients and the medical teams in one location is more efficient, benefiting patients. “Before, if we needed advice from the doctors, we had to call and wait for them to respond. This takes time. At the AMW, we just catch them in the corridors somewhere,” said Ms Hartini. Not only does this allow the team to have a strong sense of camaraderie, doctors and other professionals alike always have a good feel of the patients’ conditions, making response to any change much quicker.

The doctors, nurses, therapists, dietitians and social workers are based in the AMW - meaning they have a greater feel of their patients’ conditions and are able to respond to changes more quickly. Regular reviews at the bedside ensure that everyone is up-to-date on the state of the patient’s health.

Effective running of the AMW is critical, and efficiency is strengthened by standardising medical practice. Six clinical care pathways were drawn up for the few conditions that are commonly seen – pneumonia, dengue, skin and soft tissue infections, pyelonephritis or kidney infections, urinary tract infections, and gastroenteritis or diarrhoea, said Dr Lim.

The pathways set out steps on diagnosis such as recognising the signs of the disease and deciding if it’s simple or complicated, the tests needed, and treatments to use. Patients found to need prolonged care because their conditions are severe or complicated will be transferred to the general wards.

An Early Ambulatory Clinic (EAC) was also set up in tandem with the AMW to facilitate discharge. Patients have up to a week after discharge to see an internist for a one-off appointment to “tie up loose ends”, said Dr Tharmmambal.

The processes at the AMW are continually being fine-tuned and improved, and more conditions are added to the array the team now sees. The AMW will have more than double the number of beds from the current 67, when the new building housing the new A&E is ready. The AMW and EAC will be important integral parts of the A&E.

As with other hospital and healthcare facilities, a bigger A&E is necessary as demand for health-care services is expected to increase sharply. The Ministry of Health, in its Healthcare 2020 plan, has identified population growth, a greying population and a greater burden of chronic diseases as the key drivers of health-care demand. The size of facilities isn’t the only consideration. Health-care providers like SGH are also under pressure to build greater efficiency if they are to deal with the expected onslaught of patients in the coming years.

This story was first published in Singapore Health, Jan-Feb 2018 issue.