Report adapted from: Tan RMR, Ong GY, Chong S, et al Dynamic adaptation to COVID-19 in a Singapore paediatric emergency department Emergency Medicine Journal Published Online First: 22 April 2020. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2020-209634

KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital’s (KKH) paediatric emergency department (ED) sees approximately 180,000 patients annually. The evolving COVID-19 situation has presented unique challenges for implementing logistic and workflow changes while maintaining continuity of care.

This short review of KKH’s tertiary paediatric ED perspective and experience adapting to COVID-19 from January to March 2020 may have useful implications for paediatric EDs in other countries.

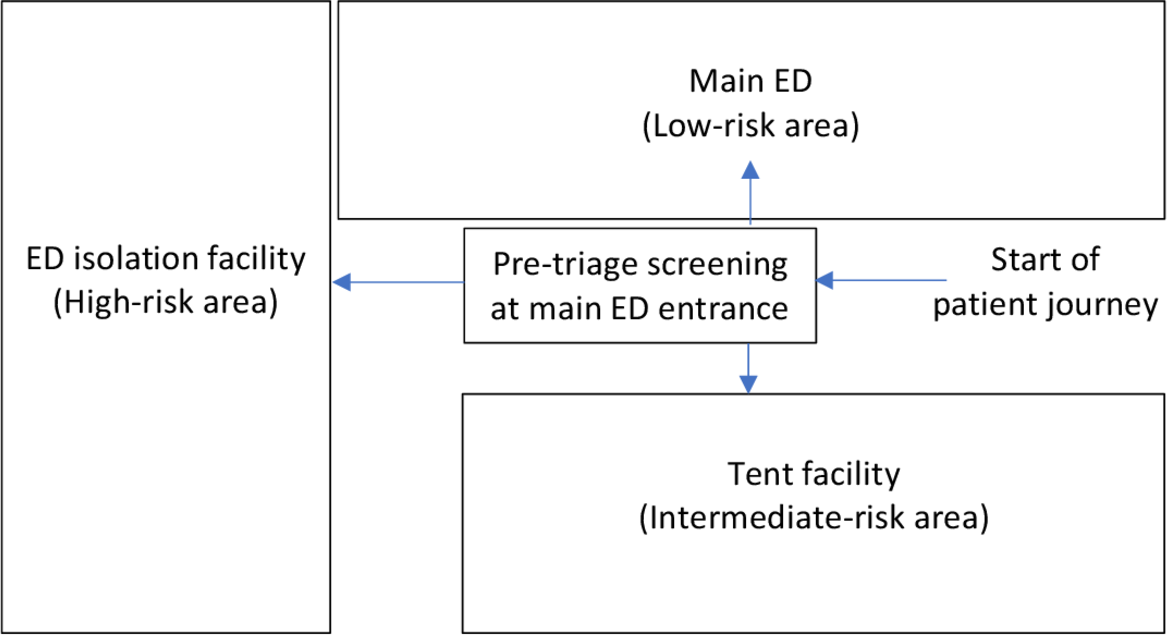

Segregation of ED into high-risk, intermediate-risk and low-risk areas

At baseline, patients were screened at triage within the main ED; patients with recent travel to China were given surgical face masks and seen in the ED isolation area. Subsequently, pre-triage screening was initiated before entering the ED and patients were segregated into three risk-stratified, physically separate areas (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Initial layout of high-risk, intermediate-risk and low-risk areas of the emergency department (ED). The intermediate-risk and low-risk areas were later switched due to space constraints and patient numbers.

A tent was built to increase capacity and we chose to see low-risk patients there as they represented the smallest category of patients that were directed to the KKH paediatric ED. Floor-to-ceiling partitions were built to cordon off part of the main ED to serve low-risk patients needing procedural sedation and X-rays, ensuring that all three areas had X-ray facilities.

It was necessary to distinguish between intermediate-risk and low-risk to balance exposure risks to patients and healthcare professionals with resource utilisation of personal protective equipment (PPE). In view of the novel virus with many unknowns, risk stratification was frequently updated based on the Ministry of Health (MOH) case definition and infectious diseases team input.

- High-risk area - Patients/caregivers with symptoms and travel history based on MOH case definition were housed in the existing ED isolation facility with negative-pressure resuscitation bay and private consult rooms.

- Intermediate-risk area - Patients/caregivers with fever or acute respiratory symptoms were issued surgical face masks and managed here.

- Low-risk area – Patients/caregivers with no travel or contact history, fever or acute respiratory symptoms were managed here.

A: ED Isolation Facility

B: Floor-to-ceiling partitions built to cordon off part of the main ED to serve low-risk patients needing procedural sedation and X-rays.

C: Extended screening area

D: Patient waiting area

Risk-adapted use of PPE for healthcare personnel

Pre-outbreak standard Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in the KKH paediatric ED was: surgical face mask and hand hygiene (alcohol hand rub) for all clinical contacts; with the addition of N95 face mask, gown and gloves for airborne/droplet-borne infectious cases in the isolation facility.

With increasing numbers of confirmed COVID-19 cases, evidence of hospital transmission to healthcare personnel in China, and possibility of ocular transmission, standard PPE was progressively enhanced with N95 face masks, and subsequently eye protection. This is similar to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended PPE when caring for patients with known/suspected COVID-19: respirator/face mask (N95 or higher-level protection for aerosol-generating procedures), eye protection, gloves and gown.

COVID-19 Testing

During the initial outbreak, COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swabs were only performed for inpatients. Outpatient testing prior to ED discharge was progressively introduced for enhanced surveillance.

The discovery of high viral loads with potential transmission from asymptomatic children highlighted the need for early identification of suspect cases. This allowed containment measures, assessment of community spread and vigilance for potential school clusters.

Testing of asymptomatic paediatric contacts of positive cases was expedited by close communication between ED staff, hospital infectious diseases team and the Ministry of Health.

The workflow required a dedicated room for ED staff wearing full PPE to perform the nasopharyngeal swab, then hand-deliver the specimen to the hospital laboratory in a double bag (to prevent transmission to lab staff).

Parents were advised as follows:

- The child was given medical leave of absence for 5 days, within which time they would be informed of the swab result.

- To self-isolate the child at home as a precautionary measure until the swab result was available.

- To bring the child back to ED if unwell or fever persisted.

Admissions Process

Initially, only COVID-19 suspect cases were admitted to a designated isolation ward. Subsequently, patients with community-acquired pneumonia requiring admission were also isolated and cohorted.

Patients admitted for urgent surgery who had an intercurrent illness with respiratory symptoms were cohorted and COVID-19 swab performed prior to surgery.

High-risk and intermediate-risk admissions were escorted by hospital security staff and patient care assistants wearing full PPE, to clear the route for patient transfer, secure the elevators and disinfect the elevators immediately afterwards.

Management of adult parents/caregivers

When children requiring inpatient admission presented with an unwell accompanying adult caregiver, further considerations included: maintaining family care as a unit, keeping one designated caregiver throughout hospital admission, age of the child, clinical acuity of both child and adult, and minimising movement of confirmed cases as part of outbreak containment efforts.

If an alternate caregiver was available, the child would be admitted with the well caregiver and the sick adult sent to the National Centre for Infectious Diseases. Otherwise, the dyad was admitted and kept together in the paediatric hospital as far as possible, except in situations where the adult was acutely ill (breathless or requiring intensive care) or had chronic medical conditions requiring adult specialist input.

Manpower considerations

To mitigate the risk of hospital transmission of COVID-19, our ED medical manpower was split, with doctors rostered into four modular teams working in 12-hour shifts to prevent cross-exposure.

Future directions

Operationalising a tiered isolation facility has highlighted several practical considerations:

- The permanent isolation facility of the main ED needs structural modifications, including anterooms for PPE donning/doffing and a separate isolation resuscitation area for non-COVID-19 infectious cases such as measles or pertussis.

- During an outbreak it is ideal to manage potentially infectious cases outside the main ED. The tent design should meet this need by replicating the following ED functions:

- PPE donning/doffing area

- Separate room for aerosol-generating procedures

- Separate resuscitation room

- Separate lead shield-equipped portable X-ray room

- Dedicated patient washroom

- Onsite pharmacy for discharge medications

- Refresher PPE training is needed even if staff have received PPE training and N95 mask fit-testing.

As we refine our understanding of COVID-19, a high degree of active surveillance in the community and dynamic reassessment of ED workflow processes, in conjunction with the hospital and nationwide public health response, can help the paediatric ED to better manage and prepare for outbreaks.

Read the full paper

here

Acknowledgements The authors thank Associate Professor Ng Kee Chong, Associate Professor Chan Yoke Hwee, Associate Professor Thoon Koh Cheng and the Infectious Diseases team; doctors, nurses and support staff of the Department of Emergency Medicine; and the Emergency Preparedness team; KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore.