A study by NCCS has made findings into the treatment options for patients with intermediate-stage liver cancer, where the tumour is too large to be removed with surgery.

For a long time, patients with intermediate-

stage liver cancer, where

the tumour is too large to be removed

with surgery, had no clear

data on which treatment worked

best.

One type of treatment directs

tiny radioactive spheres to the tumour,

while the other is an oral medication

– sorafenib – that must be

taken as long as the body can bear

the side effects.

But after seven years of research,

a team from Singapore led by National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS) surgeon Pierce Chow has

found that half the people on the

oral medication experienced side effects,

compared with just over a quarter for the radiation treatment.

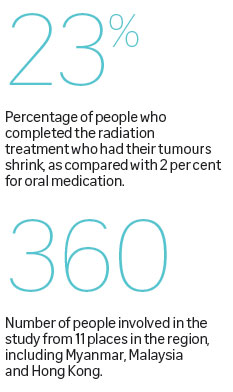

And of the people who completed

the radiation treatment, 23 per cent

had their tumours shrink, compared

with 2 per cent for oral medication.

And of the people who completed

the radiation treatment, 23 per cent

had their tumours shrink, compared

with 2 per cent for oral medication.

When the tumours shrink, it

means doctors can potentially treat

the problem with surgery or a liver

transplant.

The study, presented at a prestigious

international conference last

month, has given both patients and

doctors more information on

which to base their decisions.

Before the results of the study,

Professor Chow said a liver cancer

patient’s treatment was determined

largely by his doctor’s experience.

“It depended on which doctor

you asked or where you went,” he

said. “Without our trial, this data

would not be known.”

The study involved 360 people

from 11 places in the region, including

Myanmar, Malaysia and Hong

Kong. It was partially funded by

grants from the National Medical

Research Council.

Liver cancer is most common in

Asia and Africa, and is often caused

by the hepatitis B and C viruses or

fatty liver disease.

Around half of all patients in Singapore

are diagnosed in the intermediate

stage, where their tumours

are too big to be removed by

surgery.

The disease ranks among the top

five causes of cancer deaths here,

with around 2,500 people dying of

it between 2010 and 2014.

Associate Professor Teoh Yee

Leong, who is the chief executive of

the Singapore Clinical Research Institute

(SCRI), said the project

nearly did not come to fruition because

it was difficult to secure funding.

The SCRI was involved in the

study as NCCS’ academic partner.

While many clinical trials are typically

funded by pharmaceutical

companies, this particular study

was of no interest to the manufacturers

of either treatment mode.

“In between, there were so many

times we almost gave up,” said Prof

Teoh.

Next, the team is planning to

study how cost-effective each treatment

is, especially when the treatment

of side effects is taken into

consideration.